The Tommy gun first carved a name for itself on the streets of Chicago during the grand bad days of the “Roaring Twenties,” and later played an important part in several world conflicts. The term “Chicago Typewriter” is only one of many applied to what was, for some, an excellent fighting tool. First placed on the market in 1921, Gen. John T. Thompson’s remarkable invention quickly found its way into lawless hands, most likely led — or at least inspired — by Chicago’s bootleggers. Only later, when police forces realized their lack of comparable firepower, did law enforcement adopt the weapon.

One of the earliest marketers of the Tommy gun was the Auto Ordnance Corp., same name as the makers of two of our test guns. The first price noted was $200, quite a handful of change in the early 1920s. However, if you wanted a submachinegun at that time, there were exactly no other options worldwide until about 1928, according to Smith’s “Small Arms of the World.” The Tommy gun thrived.

The first editions of the Thompson were marvels of careful machining. These were the guns with the slotted bolt knob on top (so you could see the sights), the double pistol grip, the 50- or 100-round drum magazines, and with cooling fins cut around the rear portion of the barrel. The early Tommy guns also incorporated a friction-type mechanism (Blish theory) that was supposed to delay the blowback operation, though later tests indicated little actual delay took place, and the system was eventually dropped. The early guns also had the Cutts compensator, designed to help control muzzle climb in full-auto mode. These guns had hand-detachable butt stocks and an adjustable leaf-type rear sight. These came to be known as the Model 1928A1. Caliber was, of course, .45 ACP, but some were also produced in 9mm and 38 Auto.

Early in WWII, the Tommy was redesigned, and the new version was adopted by the U.S. armed forces in 1942 as the M1 Thompson. Gone were the cooling fins, Cutts, detachable butt stock, adjustable rear sight, and the breech-delay system with its associated oiler. The bolt knob was relocated to the right side, and the redesigned gun would no longer accept drum magazines, making do nicely with 20- or 30-round stick mags. In this guise it saw service on every theater of WWII, and most likely is still in use today by some armed forces, though perhaps not in this country.

Late in 1942 the U.S. military adopted a stamped-steel subgun called the M3, quickly dubbed the “Grease Gun” by GIs. The gun was designed to be easily adapted from .45 ACP to 9mm. Over the next two years that gun’s bugs were removed and a new version ensued, known as the M3A1. The Grease Gun saw extensive service in both WWII and the Korean War. A total of about 3/4 million were made through the Korean War, most by GM and some by Ithaca Gun Co. Among other changes, the M3A1 version did away with the charging handle, utilizing instead a finger-hole in the bolt. This gun and the Thompson fired from an open bolt. The Tommy was selective fire, but the M3 was full-auto all the time. Some users of the M3 have told us they were quite fond of the gun, and were able to control full-auto fire rather well.

Collector desirability has driven the price of original Thompsons to high levels today. If a particular gun has provenance to gangster-era use, and especially if it can be linked to specific individuals on either side of the law, the price quickly escalates to astronomical. Hence there was a ready market for semiautomatic Tommy guns, as made by Auto Ordnance. That company makes semiautomatic copies of the Thompson in several guises. We acquired both its 1927A-1C and M1 versions for our tests. We also acquired a semiautomatic version of the M3 Grease Gun, made by Valkyrie Arms of Olympia, WA.

In case you’re wondering, recoil is not a factor at all with even the lightest of these test weapons. Our three test guns all fired from closed bolts, were semiautomatic only, had fixed stocks, and barrels long enough to be legal almost everywhere. Vast quantities of mil-surplus magazines give them all 30-round capacity.

We tested with three types of ammunition: Hungarian 230-grain ball, hot Cor-Bon 185-grain JHP, and relatively light-loaded Winchester 230-grain BEB, shooting from a machine rest at 50 yards, with the exception of two loads with the M3, which we could not get to strike the target at 50 yards, so we shot those loads at 25 yards. Here are our findings.

[PDFCAP(1)]This carbine had an aluminum-alloy receiver, and had its barrel relieved of much of its weight via lathe-turned circumferential cuts. This copy of the early Thompson was fitted with the Cutts compensator and double pistol grips made of plain but strong walnut. We fitted this one with an optional drum magazine ($139) that really made it look like a “Chicago typewriter.” The later M1 design tested below didn’t accept the drum. We did some of our testing with the drum, but it proved time-consuming to take it apart to reload after every ten shots (its max), so we did most of our testing of both Tommy guns with the 30-round stick magazines ($59). There is a real 50-round drum mag available ($275) for law enforcement personnel and for export sales.

Workmanship on the M1927 was excellent. The barrel was nicely polished and blued, and the alloy receiver was comparably blacked, though in some lights it had a slight purple shade. The turning of the barrel to create the fins was outstanding machining, with the fins functional, cleanly cut, and smooth-topped. The M1927A-1C was a good example, we thought, of the original Tommy gun, but it had noticeable differences. The butt stock was not removable, a necessity to comply with existing laws. The receiver had the “belly” behind the trigger guard of the M1, where original Thompson 1928s were slimmer. The shape of the wood pistol grips was okay, but we would take a sander to them and round them more, per photos of originals we’ve seen. There were other minor differences, but all in all, this was a fine example of the Thompson, in our opinion.

If we owned this gun, we’d give the wood a better, more pore-filling finish. The wood on our sample was appropriately finished for mil-spec guns, we thought, but probably ought to have had a finish more suitable to the often fancy wood seen on originals. All three pieces of wood were securely fastened to the metal with no looseness or shaking. The wood pores were fairly open, and the wood finish was flat with no glare, which one might expect from a mil-spec firearm. There was a sling swivel on the butt stock, but none on the pistol-grip forend. The butt was fitted with a steel plate that proved to be far too slick to stay in place on the shoulder during our bench testing.

Though the magazine release and safety were set up to favor right-handed shooters, lefties could get at these controls by bringing the thumb onto the left side of the action. The safety (on both samples of the Thompson) was in the form of a button with a rod-shaped lever. Rotating it through 180 degrees from pointing rearward to pointing forward got it to the fire position. With it in the safe position, it was extremely difficult to pull the bolt handle fully rearward, as in “lock and load.” That was with the piece cocked. With it uncocked, it was impossible to draw the bolt rearward far enough to chamber a round with the safety on. With an empty magazine in place, the bolt stayed open when it was drawn fully rearward, so that’s where it stayed after the last round was fired. With the magazine out of the gun, it was necessary to press upward on the bolt block with one hand while drawing the bolt fully rearward. This was not an easy trick, we found, because of the strong bolt spring of this blow-back design.

The trigger pull was long, spongy, and hefty, breaking ultimately at 11.0 pounds. We liked the rear sight, which gave the option of either a tiny notch in a flat-top blade, or a decent aperture on a ladder. The aperture changed elevation by means of a spring-loaded catch. We used the aperture for all our testing. Actually, the wide notch in the bolt served as a rough and very fast rear sight, and no doubt would have been fine for much of the original design’s full-auto use. The front sight was integrally machined as part of the Cutts compensator, and presented a solid flat-top post to the shooter.

Loading the magazine was a breeze. The cartridges went in easily as we pressed them down between the lips. This was in great contrast to the M3, the magazine of which was extremely difficult to load. The magazine fit snugly into the lips in front of the trigger guard, and a brisk poke upward snapped it into place. It stayed put and didn’t rattle, yet was easy to get out. Both Thompsons felt about equal in magazine fit. With the safety on, a tug on the bolt knob, then letting it fly forward, got a round into the chamber. The path to the chamber was in the form of a huge funnel, with the rear edge of the chamber rounded to permit the cartridge to enter easily. With a few exceptions noted below, all rounds got into the chamber easily with both Thompsons.

We found the aperture rear sight of the 1927 to be easy to use. With a few rounds we got centered for elevation, and didn’t need to change the windage — which we couldn’t do without bending something. Bullet strike was within an inch or two of center for windage with all loads. As noted, we had some trouble holding the butt in place on our shoulder when shooting from the bench, but the gun performed reliably, with one exception. The Cor-Bon loads proved to be too hot for this gun, as it was set up. The 185-grain JHP Cor-Bon bullets come out of a 5-inch pistol barrel at 1,150 fps, but they came out of the Tommy at about 1,450 fps. The bolt was knocked rearward so hard it knocked up the bolt catch. Of three shots fired in this gun with that ammo, two locked the bolt back and one caused a failure to feed. We quit testing that ammo in this gun (though we found it worked perfectly in the M1). The light Winchester BEB target loads and the Hungarian ball functioned perfectly. [PDFCAP(2)], running on the order of 4 inches at 50 yards. The stiff trigger didn’t help, but our overall feeling from testing two versions of this gun is that they’re not exactly tack drivers.

[PDFCAP(3)]All steel and very heavy, the M1 Thompson had a fatter bottom on its action, similar to the original Thompson M1. The wood finish was probably close to original mil-spec, looking like an oil finish that clamored for more linseed oil, to be applied by the “soldier” (that’s you) slowly and lovingly over lots of time.

The round barrel was turned with a tapered step halfway down its 16.8-inch length. The muzzle had a nicely turned fillet and step leading to the front sight, which was held in place with a roll pin driven crosswise beneath the front blade. The receiver showed excellent workmanship, with flat sides and properly broken corners.

The receiver appeared to have been carefully wire brushed prior to bluing, and the result was an even matte finish that complimented the gun well. The well-protected rear sight was securely screwed to the receiver. It was in the form of an aperture that mated well with the post front sight. The sight picture was essentially perfect, though there were no adjustments possible, short of bending or filing things.

The 30-round magazine fitted well into a slot at the front of the action, and was securely held by a spring catch which had a lengthy extension leading to just behind the trigger, where it could be operated by the right thumb. The trigger, as fitted to both Thompsons, was well shaped and well fitted. As with the previously tested gun, the M1’s trigger pull was vague until we got the hang of it, and then could feel a slight hesitation just before it broke. It broke at 10.5 pounds, which we thought was excessive.

Recoil was nil. The report was not all that loud compared to, say, a .308 rifle, and because of the distance of the muzzle from our ears, the noise seemed far less than the noise from the same round fired in a pistol.

Our first five shots, shooting from 25 yards kneeling, indicated good accuracy potential. The group was dead center for windage but slightly low, which would permit the owner to file the front sight to zero the gun to his chosen load. Unfortunately, we did not get any better accuracy from this version than from the 1927, though it was probably enough in both cases, for just about any use to which this gun might be put. Even marginally better shooting conditions would almost certainly have benefited our accuracy results.

Much of what we said about that other Thompson is applicable here. Workmanship throughout seemed to be excellent. The wood was well-fitted and tight, the metalwork was way more than adequate, the finish was appropriate, and the whole gun seemed to have had good attention paid to its assembly and all its details. There were wide sling swivels securely attached to the forend and butt stock, and again the butt plate was too slick for us.

We had almost no problems with the M1. One round failed to chamber, early in our testing. We could not tell if the round had hung up on the chamber or if the extractor had failed to slip over it. It never happened again. The M1 handled the hot Cor-Bon ammo easily. As noted, the sight setup would permit filing down the front sight to get elevation where you want it with your best load. Accuracy of the M1 was okay, on the order of 3.5 to 4 inches at 50 yards. We would have liked more. The overall weight of 11.5 pounds might be a bit much for all-day offhand work.

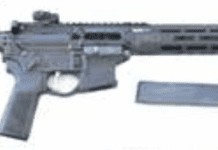

[PDFCAP(4)]Per the company’s website, this is a “…faithful re-creation of the venerable M3A1, using many original US GI parts.” Each gun comes with a 30-round magazine, and has a 16.5-inch barrel. Short dummy barrels for display are available for $60, and if you want the gun to look right, you’ll need one. In fact, this gun is all about looking right. The M3 was full-auto only, which of course this one is not. The wire stock of originals slid forward, and that, combined with the short original barrel, made the gun much more compact and more useful in tight spots. With its fixed stock and long barrel, the Valkyrie M3 was almost as long as the Tommy guns.

The overall look was a good example of the way an efficient firearm ought to look, we thought. The finish was Parkerized dark gray. The metal work was excellent, with sides flat or round as appropriate, and with no sharp corners or edges anywhere. The long barrel and fixed wire stock seemed inappropriate, and of course they were, but at least you get to own a close copy of the Grease Gun.

That stock and long barrel make ownership possible. The clever positioning of one of the takedown pins made it look a little like the original stock-release button of original M3s. The wire was actually welded to the main tube of the gun, and there was no forward loop for the wire if it could have been moved.

Beneath the dust cover, which must be open during firing, lies the bolt. There was a finger-notch in it for charging the chamber. This one fired from a closed bolt. The left side of the main body held two sling loops, and there were crude iron sights welded to its top. The rear sight was a simple but strong aperture of bent sheet metal. The front sight was a flat-top post welded to the top of the barrel retention “nut.” Though the sight picture was clean and efficient, the sights put all bullets way low, so the front blade needed lots of filing to get the bullets to hit closer to where the sights looked. Windage was fine.

The pistol grip and lower receiver were of aluminum, though the main tube, bolt, and remainder of the gun was of steel. The trigger and its guard were steel. The mag housing was also of steel, as was the button release on the left side. The magazine was original GI, we guessed. It was well made and held 30 rounds. It went into the gun positively, stayed put, and was easy to get out. It formed a natural grip for the gun. However, the mag was extremely difficult to load. It was necessary to press all the previously loaded rounds down with the incoming round, and then push that new round rearward under the mag lips, much like loading a 1911 magazine, but not as easy. It was possible to press down on the stack of ammo with a tool, such as the wire butt stock, but that didn’t make it much easier for our unaccustomed hands.

The grip panels were perforated metal, and were actually comfortable. The forward hand generally grasped the magazine, but we suspect it may have been better to place the left hand just behind the mag around the lower action. From that position it would be possible to carry the gun cocked and locked, with the left thumb on the safety, ready to move it when the gun was needed.

The safety was entirely out of reach of our right thumb unless we turned the gun 90 degrees and reached far forward with the right thumb. The safety would not go on unless the action was cocked. We note that while the original M3A1 had a protector ring around the magazine-release button, this one didn’t have it. However, we didn’t feel it needed it except perhaps cosmetically. We appreciated being able to remove the mag with ease.

There were two cross pins beneath the main barrel of the gun. They had ball detents so they won’t fall out. Removing them permitted the near-instant taking down of the gun. The entire lower portion of the gun came off, which proved to be an aluminum housing that held hammer, sear and trigger, and the trigger-blocking safety assembly. Unscrewing the barrel permitted removal of the bolt with its movable firing pin.

We found it hard to cock the bolt with our finger. We used a screwdriver. We recommend the use of some sort of tool on the bolt to help you safely charge the gun or make sure the chamber is clear, unless you have exceptionally strong fingers, short fingernails, and some experience with this system.

Once the mag was loaded and inserted into the gun and the bolt cocked, all the rounds fed unfailingly into the chamber.

There were no problems with feeding, firing, or ejection whatsoever, no matter which type ammo was in the gun. The trigger pull was an absolute delight, breaking cleanly at about 4.5 pounds, and most of that pressure was used in getting past the first stage of the two-stage pull. The sight radius was short and the aperture large, so we didn’t expect great groups. We found that the ball and Cor-Bon loads struck way too low for bench testing from 50 yards, so we moved up to 25 and by interpolation, got 3-shot groups from 6 to 8 inches at 50 yards.

Gun Tests Recommends

Auto-Ordnance Model 1927A-1C, $977. Our Pick. We liked the aluminum-framed 1927A-1C better than the all-steel M1 because it was a less-hefty gun. At 9.0 pounds It had more than enough weight for any .45 ACP load. We wouldn’t shoot hot loads in it, based on our experience with the Cor-Bon ammo. We liked the fact that this one would accept the neat-looking drum magazine, which would be mandatory, we thought, for display, even though it held only ten rounds. That fact made the drum mag nearly useless for the field, we thought, because loading the drum magazine required taking it apart, just like originals. If it were possible to load 50 rounds it might have been worth it, but the 30-round stick magazines were easy to load and held enough ammo. The later M1 Thompson worked well enough during WWII with 30-round stick magazines. We did not notice any increase in noise level nor in recoil reduction from the Cutts, though we probably missed those details because of our testing in bitterly cold and humid weather. The Cutts has to have worked, we figured, because though this gun weighed far less than the M1, felt recoil was identical. We thought this was the most desirable of the Thompsons because of its slick air-cooled looks, lighter weight (by 2.5 pounds), and better sights. We suspect most buyers will agree, unless they’ve spent lots of time with the later, simpler, M1 and simply must have one of those, or must have one with a steel receiver.

Auto-Ordnance M1 Thompson, $935. Buy It. We would not choose the M1 over the 1927, but could see no reason to reject it. The gun worked well, looked great, and was, to our eyes, a close copy of the full-auto “real thing” for a fraction of the cost. We’d work on the trigger if we owned either of the Thompsons. We also would diligently anoint the wood with linseed oil. The wood grain of the M1 looked pretty good in outdoor light, and we thought rubbing linseed oil into it would pay long-term dividends to its owner. If you’re in the market for a later-type Tommy gun, this one might do you quite well.

Valkyrie Arms M3-A1 Grease Gun, $750. Buy It. Though there were no problems and the gun worked well, frankly we could see little reason to own one of these. Yet the Valkyrie M3 and Auto Ordnance Thompsons are all about nostalgia, about letting us experience things similar to the way they used to be. Anyone who fired a WWII-era Grease Gun would be pleased to shoot this new version, we suspect. The gun worked well, so who are we to tell you it’s not needed. If you want one, we suspect you’ll be happy with it. To be sure, it would be a fine home-protection weapon at the very least. It shot reliably, and some work on the sights would get the gun printing acceptable groups as far away as you’d ever want. That makes for a lot of fun with the Grease Gun. Without doubt, these semiauto sub-guns are, each and all, a whole lot of fun, and seem to be durable goods as well. That might be all the justification you need to buy one.