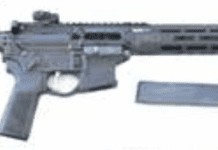

The Marlin Model 9 is compact, light in weight, and more accurate than a 9mm duty pistol at longer ranges. It’s able to fire the same service-pistol ammunition at a higher velocity, and it recoils far less than a 12-gauge shotgun. In addition, if the duty pistol happens to be a Third Generation 9mm Smith & Wesson, its magazine is interchangeable with that of the Model 9.

These factors have contributed to the growing popularity of the Model 9 as a law-enforcement and home-defense weapon, especially since the carbine is also manufactured in .45 ACP and readily accepts M1911 mags.

The primary problem you’ll encounter with the Model 9 is one it shares with all other blow-back firearms—it gets dirty fast. To ensure the gun’s proper functioning, 250 to 300 rounds is about the limit between clean-ups, although a dry film lubrication after clean-up can extend that limit to some extent.

The basic take-down for cleaning is very simple. Turn the gun upside down, then loosen the front and rear take-down screws until the barreled action can be removed from the stock. The screws are captive and remain in the stock. To remove the trigger group, check which side of the receiver carries the serial number, and drift out the two take-down pins from that side. The bolt stop will fall free at this point, so be prepared to catch it. Use your forefinger to pull the bolt slightly to the rear, and begin to lift the muzzle end of the breech bolt. This frees up the charging handle for removal and gives you easy access to the recoil spring and guide for their removal. During the take-down, always check out the buffer assembly (the nylon pad built in the receiver where the bolt catches on its rearward travel). If it shows signs of excess wear or looks mashed, replace it.

Normally, that’s as far as you have to go in prepping a Model 9 for cleaning. Any Model 9 owner can do it, and that’s the cause of the number-one complaint heard about the carbine. The guy will walk in your shop, plunk the gun down and tell you, “My bolt won’t hold open after the last shot anymore.”

The reason it doesn’t is the small bolt-stop spring your customer lost when he disassembled the gun. It is located on the bottom of the receiver toward the front. Without it, there’s no tension on the bolt stop, and the hold-open feature fails. The cure is a new spring. (I suggest you put a dab of grease on it to hold it in place during reassembly.)

The next most common complaint is failure to feed. It happens a lot, and is usually due to improper reassembly. The feed ramp, which is part of the trigger group, must be positioned back in the gun under the barrel—not behind it. If it isn’t, cartridges will stub on their way out of the magazine. The Model 9 owner’s manual doesn’t make this fact crystal clear, stating only that if the feed ramp is not pressed rearward and the holes in the bolt stop are not properly aligned, the action will not reassemble. This is true, but the primary reason Model 9s get returned to Marlin for feeding problems is simply an out-of-place feed ramp. It’s something you can correct in about 10 minutes.

If it’s not the feed ramp, the probable cause for failures to feed is ammunition. The Model 9 is designed to operate with standard-velocity loads. Due to its heavy bolt, subsonic 9mm rounds won’t function the carbine. Higher velocity rounds will function in newer Model 9s, but such ammunition in older versions of the carbine creates feeding and bolt hold-open problems.

In these older guns (I’m only talking two or three years old), the magazine spring is weaker and the bolt hold-open lever not as firm. High-velocity ammo causes the bolt to cycle faster than the old spring can keep up with it, resulting in feeding problems. This problem is compounded by the spring’s inability to bring the follower into place in order to cam up the hold-open lever. The lever takes a lot of abuse from the bolt and vice versa. Eventually, feeding failures are accompanied by failure of the bolt hold-open feature. Since the bolt is restricted to factory repair only, there’s nothing you can do but send the gun back to Marlin.

The manual hold-open on older guns, activated when the bolt handle is pulled back and pressed into a slot on the left hand side of the receiver, may also require factory service. Rough handling can cause premature wear on that setup, leading ultimately to the failure of the manual hold-open. If you spot excessive wear in the receiver slot, send the carbine in to Marlin. They’ll update it with the new-style trigger housing which has a built-in manual hold-open. Chances are they’ll replace the bolt while they’re at it. The complete update costs $35 plus $5 shipping.

You’ll also have Model 9s coming into your shop because of crimped cases. It happens will all brands of ammo—especially with reloads. The edge of the case is crimped at the mouth and your customer wants to know why. The reason is that Marlin uses a short chamber on the Model 9. Though within industry specifications, it has been cut shorter to enhance the firing-pin protrusion and assure 100-percent ignition. Marlin discourages, and I concur, any attempt to lengthen the chamber. Unless you are experienced in such things and have reworked chambers successfully in the past, trying your hand at this one can cause serious functional problems.

The other case-related complaint is denting. Again, it’s more frequently heard from reloaders. You can safely tell them their brass is being dented by the bolt handle on ejection. The Model 9 houses a high-speed mechanism, banging very rapidly around a very large bolt. The way the Model 9 was designed and built causes the dents, and there’s nothing you—or the factory—can do about it. Grinding down the bolt handle won’t help, and cutting it off will make it just about impossible to charge the gun.

Before you think that everything I’m talking about requires a trip to the factory, there are some matters you can take care of in the shop.

Magazines that stick in the housing can be fixed with relative ease. Smith & Wesson Third Generation and Model 9 magazines are advertised as being interchangeable, but you’ll come across pistol mags that hang up in the carbine. Most of the time, it will be an aftermarket bargain that is out of specification. Less frequently, it will be a Smith & Wesson. If you take a close look at a Model 9 magazine, you’ll see a 45-degree bevel at the top rear, or primer, end. Filing that bevel in a factory-made Third Generation magazine will eliminate the sticking. It may or may not do the same with a cheaper magazine.

Trigger Housing and Trigger Group

The nature of the Model 9’s recoil operation causes the trigger housing and group to get dirty faster than other guns will. When the bolt travels back, it deposits dirt and carbon into the housing.

It isn’t necessary to separate the trigger group from the housing for cleaning purposes, but care should be used in selecting the cleaning agent to be used in the process. The Model 9 housing is made of ABS plastic, not nylon. It’s good, strong stuff, but it can be weakened by organic-based solvents, particularly toluene and trichlorethylene. Carburetor cleaner will dissolve ABS right before your eyes. Other organics, such as paint thinner, kerosene, and bore solvents, don’t have such a dramatic immediate effect on the plastic, but can damage it over a period of time. Do your cleaning of the housing with alcohol, either methyl or denatured. You can safely soak ABS in alcohol for days to loosen crud, and if necessary, flush it out with an alcohol-filled squeeze bottle. By the way, the Model 9 isn’t the only firearm around with ABS components. If you have any doubts about whether or not a part is made of ABS plastic, avoid the organics when you’re cleaning it.

The trigger group contains no plastic, and rarely presents problems unless it’s been taken apart by your customer and improperly reassembled. If any parts have been lost in the process, you can order them from Marlin (with a few exceptions).

The factory method of disassembling the action goes like this (all pins, except three, drift left to right and reassembly is in reverse order): First, drift out cross pins at the front and rear of the lower receiver. Remove the plastic housing downward, which will release the bolt hold-open lever. Remove the hold-open lever spring from its recess in the receiver. Pull the bolt slightly to the rear, lift at its front and remove the cocking handle. Controlling the recoil spring, continue to lift the bolt until it clears, then ease it out frontwards. Remove the recoil spring and guide. The firing pin and firing-pin spring are retained by a vertical pin in the bolt. If replacement is needed, the pin is driven out upward. The extractor pivots and is retained by a pin which can be driven out upward.

Removing the extractor to the right exposes the extractor spring, which is then removed from its recess. The vertical pin serving as a pivot for the loaded-chamber indicator and its coil spring can be driven out upward. The nylon recoil buffer is pried out of its recess toward the front. Insert the magazine, insert a small drift punch into the hole at the rear of the hammer spring strut, ease the hammer down to its fired position, and remove the magazine. Remove the clip on the left of the hammer pivot, then remove the sideplate. Control the trapped hammer spring while removing it, the strut, and the spring baseplate. While restraining the sear, push on the hammer pivot to remove the right sideplate. Remove the cartridge guide and its spring. Remove the hammer. Remove the sear and sear spring from the top of the trigger. Tip up the trigger to clear it from its spring and remove.

Push the safety out upward and remove while keeping your fingertip over the hole containing the safety-detent ball and spring, then remove the ball and spring. Depress the magazine safety to remove the trigger-block lever. The magazine safety and spring are held in place by the forward of the two ejector cross pins. Unless the ejector requires replacement, leave these parts in place. Drift out the trigger-spring cross pin and remove the spring, then remove the magazine catch by unscrewing the slotted button. Take the button and spring off to the left and the catch to the right. Remove the sear/disconnector in the trigger by drifting out the cross pin.

Marlin uses special jigs to hold the trigger-group parts in place when putting them back together. Since these tools aren’t available to the gunsmith, think of other ways to simplify the job. What I do to stay out of trouble when I first encounter a new gun is use a Polaroid camera with a close-up attachment as I work my way through the disassembly process. Backtracking through the photos as you reassemble is a great way to be sure everything gets put back in the right place.