While it’s true that a self-loading pistol carries more rounds than a revolver, a pistol is more prone to malfunctions. A single action revolver requires cocking of the hammer before each round can be fired and considerable time to reload. That leaves a double action revolver.

What kind and why? A double action revolver is easy to learn to shoot. It is totally reliable as long as it is decently maintained and the quality of its ammunition remains high. A short-barreled revolver is easily secreted in a bedside table drawer or on one’s person in states that allow law-abiding citizens to carry concealed. Many think that it should hold six rounds rather than five. What caliber? A .22 isn’t powerful enough, a .44 Magnum is too powerful unless you’re really used to it.

We’d suggest a wheelgun chambered for the .357 Magnum to be your best, first choice. If, after firing it at a range the first few times, the blast and recoil of a .357 bothers you, you can download to .38+P ammunition. Most police carrying revolvers as their back-up weapon opt for +P, so you can consider it suitably effective. For target use or practice, you can safely fire plain old .38 Specials to your heart’s content in a revolver made to digest the .357. But firing the more powerful .357 Magnum or .38+P in a .38 Special revolver would be a disaster.

When you put all of these attributes together, you see why a compact six-shot .357 Magnum double action revolver maybe the ideal self-defense handgun. Three such handguns are the subjects of this test. They are the Smith & Wesson Model 65, the Taurus Model 606 and the Rossi Model 877. The first two revolvers earned our approval, but the third one didn’t make the grade.

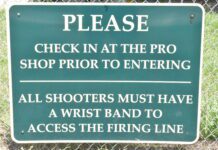

How We Tested

During this head-to-head evaluation, we fired 200 rounds of commercial ammunition through each revolver. Accuracy testing was conducted outdoors at 15 yards using a padded pistol rest. We fired five consecutive 5-shot groups with each of three brands of ammunition: Winchester 110-grain jacketed hollow point, Federal Hi-Shok 125-grain jacketed hollow point and Remington 158-grain lead semi-wadcutter. Accuracy and velocity results are detailed in the accompanying performance table. When the accuracy phase was completed, each revolver was fired from a two-handed unsupported position to detect functional flaws that could hinder its performance during field use.

The results of our evaluations follow:

Smith & Wesson Model 65

This stainless steel Smith & Wesson was brought onto the market in the 1980’s as a law enforcement firearm, but it quickly became a popular choice for the private citizen who wanted a concealable .357 Magnum revolver. The Model 65 we acquired for this test came with a 3-inch heavy barrel, which was the shortest available. Other features of this $435 double action revolver included a fluted six-shot cylinder, fixed sights and an Uncle Mike’s Combat grip.

Physical Description

We considered the Model 65’s fit and finish to be average. All of its stainless steel surfaces had an even matte finish. The hammer and the trigger were color case hardened. Polishing and tool marks were found along the barrel and in the flutes of the cylinder. However, no sharp edges or other cosmetic flaws were found. The lockwork was tightly fitted and well-timed, though the mainspring strain screw was loose and required tightening prior to firing.

Smith & Wesson equipped this revolver with a two-piece black rubber grip that covered the entire grip frame. It had molded checkering, palm swells and three finger grooves. Both halves of the grip were securely fastened in place with one slotted screw. Grip to metal mating was good, without any noticeable gaps.

Our Judgments

During live fire testing, the Model 65 functioned reliably with the three brands of ammunition we used. The ejector rod had a smooth throw. Although it didn’t provide full-length extraction, fired cases cleared the cylinder when the muzzle was raised and the rod was rapped briskly. This revolver’s passive safety, an internal hammer block and rebound slide system, prevented firing if the trigger wasn’t pulled all the way to the rear.

Since this Smith & Wesson was the largest and heaviest handgun of the test, it was the least compact and hardest to conceal. However, it was also the easiest to handle and control. Kick and muzzle jump were noticeably milder than those of the other magnums tested, which made follow-up shots the fastest. The comparatively long rubber grip afforded a stable grasp and aided in lessening felt recoil. Our shooters said the revolver was slightly muzzle heavy, which is an asset on a magnum revolver, and pointed dead-on target.

The cylinder release was a checkered thumbpiece located behind the cylinder on the left side of the frame. When pushed forward, it allowed the swing-out cylinder to be opened. Right-handed shooters could readily operate the release with the thumb of their firing hand.

We felt the movement of the ungrooved 5/16-inch-wide trigger was good but not great, which is typical of most Smith & Wesson revolvers. The double action pull had a slightly gritty feel just prior to letting off at 11 pounds. In the single action mode, the trigger released cleanly at 4 1/2 pounds. Both pulls had a moderate amount of overtravel.

In our opinion, the Model 65’s fixed, stainless steel sights provided the best sight picture of the test. But, due to the lack of contrast between the front and rear elements, they were more difficult to acquire than blued sights. The front was a relatively large 1/8-inch-wide blade with a serrated face. It was integral with the front top of the barrel. The non-adjustable rear was a groove cut into the top of the frame with a notched face. This arrangement’s point of aim was at or near the point of impact at 15 yards.

With the right ammunition, we considered this Smith & Wesson’s accuracy to be very good for a short-barreled magnum revolver. It seemed to prefer lighter-weight bullets. At 15 yards, it produced five-shot groups that averaged from 1.98 inches with Winchester 110-grain JHPs to 2.80 inches with Remington 158-grain lead semi-wadcutters.

Due to the Model 65’s 1-inch longer barrel, its velocities were by far the fastest of the three revolvers tested. In fact, this .357 Magnum’s average velocities were at least 109 to 134 feet per second higher than those of its competitors. Speeds measured from 1,185 feet per second with the Remington 158-grain load to 1,405 feet per second with Federal 125-grain JHPs.

Taurus Model 606

One of Taurus’ newest revolvers is the Model 606. It is a small double action .357 Magnum with a fluted six-shot cylinder and fixed sights. This model’s 2 1/8-inch barrel has a shroud that protects the ejector rod. The stainless steel version has a suggested retail price of $319. Options include a blued finish, a concealed (spurless) hammer, factory barrel porting and the manufacturer’s security system.

Physical Description

Workmanship of the stainless steel Model 606 we acquired was, in our opinion, below average. Most of its surfaces had a polished mirror-like finish. Tool marks were noted on the frame, barrel and in the cylinder flutes. The sideplate had several large gaps, raised metal edges, and was not seated properly against the frame. Edges of the trigger were sharp. However, the revolver’s performance wasn’t affected by these numerous flaws. The action was satisfactorily fitted and properly timed.

The black Santoprene grip provided on this Taurus had pebble-type texturing, 3 finger grooves and a finish with a somewhat tacky feel. It covered the entire grip frame and was securely fastened with one screw. Despite a small gap at the back of the trigger guard, we thought the grip to metal fit was good.

Our Judgments

In operation, the Model 606 fed and fired the ammunition we tried without a hitch. However, the ejector rod had a rough throw and wasn’t long enough to provide full-length extraction. Occasionally, one or two empty cases weren’t pushed all the way out of the chambers and had to be removed by hand. Also, after firing about 100 rounds, the retaining screw on the cylinder release shot loose and caused the release to fall off the gun. A little Loctite cured the problem.

Our shooters felt this Taurus’ size and weight afforded a decent compromise between conceal-ability and controllability. It was easier to carry and conceal than the Smith & Wesson Model 65, but the Model 606’s felt recoil was noticeably heavier. Although the gun could be targeted quickly for initial shots, recovering for follow-up shots was comparatively slow. Shooters with small and medium-size hands said the synthetic grip afforded a good grasp, but those with large hands thought it was too short. This revolver sat evenly in the hand and tended to point high.

The cylinder release was located at the rear of the cylinder on left side of the frame. Right-handed shooters could reach and operate the release with their dominant thumb without shifting their grip. The internal safety, a passive transfer bar system, allowed firing only when the trigger was pulled fully to the rear.

We considered the double action pull of the Model 606’s ungrooved 3/8-inch-wide trigger to be very good. It was smooth, though a slight amount of spring stacking could be felt, and let off at 9 pounds. However, in our opinion, the single action pull was a little too light for novice shooters. It had no slack and released smoothly with only 2 1/2 pounds of rearward pressure. There was very little overtravel.

Our shooters felt the fixed, stainless steel sights were difficult to rapidly acquire, due to their lack of contrast and small size. The front was a serrated 1/8-inch-wide ramp blade, which was integral with the top of the barrel. The rear was a groove in the top of the frame with a notched face, making it non-adjustable. Unfortunately, this sighting system’s point of aim was 8 inches higher than the point of impact at 15 yards. We compensated for this deviation by adjusting our aiming point.

After our testers figured out how much Tennessee elevation was needed to hit the target, they found the Model 606’s accuracy to be above average for a revolver of this type. It produced five-shot groups that averaged from 2.33 inches with Federal 125-grain JHPs to 2.80 inches with Winchester 110-grain JHPs at 15 yards.

Chronograph testing showed that the Model 606 yielded average muzzle velocities of 1,058 feet per second with the Remington 158-grain load to 1,271 feet per second with the Federal 125-grain ammunition. This level of performance was, in our opinion, satisfactory for a short-barreled .357 Magnum revolver.

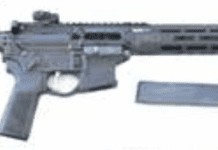

Rossi Model 877

The Brazilian-made Rossi Model 877 is imported by Interarms. It is one of the lightest and least expensive six-shot stainless steel .357 Magnums on the market. This $290 double action revolver has a 2-inch barrel with an ejector rod shroud. Like the other guns in this test, is equipped with fixed sights and a rubber grip. A matte blue version of this revolver, the Model 677, is also made.

Physical Description

Our evaluators considered the Rossi’s fit and finish to be poor. In spite of its brushed stainless steel finish, very noticeable polishing marks were visible on the flats and around the edges of the frame. Rough tool marks were evident on the trigger guard cuts. The sideplate’s edges had some areas that were either raised or chipped. A very sharp edge was noted on the front of the barrel shroud.

The cylinder and lockwork were properly timed. However, we noted one major fitting flaw. Some areas of the cylinder’s extractor star were very rough, which sometimes caused the hand to drag and bind the action. A 1/16-inch-wide gap between the barrel underlug and the frame was unsightly and made the barrel appear to be too small for the frame.

On this model, Rossi provided a two-piece rubber grip that covered the entire grip frame. It had a smooth finish, molded pebbling and three finger grooves. Although the grip was securely fastened with one screw, it didn’t mate with the frame very well. There were some small gaps and puckering at the seams.

Our Judgments

At the range, our Model 877 functioning wasn’t 100 percent reliable. Its action was often very hard to cycle due to the aforementioned poor fitting of the cylinder’s extractor star. The short ejector rod worked smoothly, but it routinely failed to completely extract one or two fired cases. Shooters had to finish removing them manually.

Manipulating the cylinder release on the left side of the frame wasn’t a problem for right-handed shooters. When pushed forward, the release allowed the cylinder to be swung open. The internal safety, a passive hammer block and rebound slide system, prevented firing when the trigger wasn’t pulled all the way to the rear.

This evenly balanced revolver’s lighter weight make it easier to carry for any length of time than the Smith & Wesson or Taurus in this test. However, it recoiled the most. The rubber grip’s length was too short for shooters with large hands, and its slim top was a hindrance when trying to establish a non-slip grasp. Consequently, we found that firing rapid follow-up shots was quite difficult. Pointing and target acquisition were very quick.

In our opinion, the movement of this Rossi’s grooved 5/16-inch-wide trigger was only adequate. The double action pull had a gritty, inconsistent feel and let off at 13 pounds. After a noticeable amount of creep, the single action pull released at 4 1/4 pounds. Overtravel was moderate.

None of our shooters felt the fixed, stainless steel sights provided a satisfactory sighting reference. Only the bottom half of the ramped front blade’s face was serrated, so the top portion glared in direct light. The non-adjustable rear consisted of a groove in the top of the frame with a notched face. At 15 yards, we found that this arrangement’s point of aim was about 8 inches to the right of the point of impact.

Using Kentucky windage (shifting the aiming point enough to hit the target), we found the Model 877’s accuracy to be adequate for its intended use. Average five-shot groups measured from 2.23 inches with Federal 125-grain JHPs to 3.18 inches with Winchester 110-grain JHPs at 15 yards.

This Rossi’s performance should have been better. Its muzzle velocities were below average for a .357 Magnum revolver with a 2-inch barrel, and the slowest of the test. In fact, they were 28 to 76 feet per second slower than those of the Taurus Model 606.

If the 65 wasn’t easily the smoothest of the three, you had a skewed sampling of the three. I have found interarms era Rossi revolvers to be quite nice and above any generation Taurus I have owned.

1) To avoid the “disaster” of shooting 357mag ammo in a 38spl revolver, (as you state in the beginning of your article), the 357 mag cartridge case was made 1/10 of an inch longer than a 38spl cartridge case. The 357 mag case won’t fit in a 38spl cylinder, let alone cycle in one.

2) If a 38spl revolver is rated for 38spl +P, why would shooting 38spl +P in it be a disaster?

3) The model 65 came to market in the early 1970’s not the 1980’s.

4) I agree with Jeremiah, the Rossi revolvers imported by Interarms back in the day were made with a higher degree of quality than the current Rossiaurus guns that are being peddled today.

you can’t compair the S&W65 with the other Rossi or other Mfg’s.

The S&W revolvers are a head above the others. Shoot them both and feel the differemce!