The snubnosed revolver is and has been one of the most usable firearms in modern history. With barrel lengths typically measuring from 2 to 2.5 inches, their simplicity and concealability are invaluable. That said, for most of this genre’s lifetime, these guns topped out in power at the .38 Special level, and they carried only five rounds. It’s easy to see why: Not having to chamber the longer .357 Magnum cartridge saves length and bulk, since the lighter .38 load means less material is needed to reinforce the frame.

Adding (at least) a sixth chamber and magnum capability is what our test trio here is all about. The K-frame is the basis for the Smith & Wesson Model 66, $545. Taurus’s 617, $355, is actually a little smaller while offering a seventh shot. With Taurus’s acquisition of the brand, Rossi returns to market with a six-shot .357, the Model 461, $298. The Smith & Wesson 66 is available in stainless only. (Its kissing cousin the model 19 comes in blue.) The Taurus 617 is available stainless or blued, with or without porting. We chose blued without holes. The Rossi 461 is blued, but it can be had in stainless (the 462).

It is about time Rossi made a comeback, in our view, because we think recently reported downward trends in handgun purchases have a lot to do with price. Actually, in light of the amount of time Smith & Wesson is spending in the doghouse because it got into bed with former President Bill Clinton, we are surprised more manufacturers of wheelguns haven’t come out of the woodwork.

Perhaps there is more to this test than a simple matchup of three revolvers. With Smith & Wesson on the ropes, we have to wonder, do competitors think they can cruise to higher sales based solely on a perceived public preference for revolvers built by anyone but Smith? Or, will discerning gun makers recognize Smith & Wesson’s overwhelming track record of performance and challenge them not only on 2nd Amendment issues but with quality products as well? Perhaps the following evaluation will offer clues as to how Rossi and Taurus International will proceed.

Range Session

In collecting accuracy data, our first consideration was distance. We settled on 15 yards from a sandbag rest. Additional ground rules called for five-shot groups fired both single- as well as double-action. As it turned out, the choice of ammunition told us more about our three guns than any set of shooting drills could ever do.

Simply the blast of the .357 Magnum cartridge alone was enough to rattle the timbers of each revolver and reveal both strengths and weaknesses of each design. When a problem arose we investigated by firing a wider variety of rounds in both .357 Magnum and .38 Special. Short-barreled guns with cylinder gaps to boot are loud and sometimes dirty. In an attempt to make our snubbies more livable, we chose what we hoped would be effective but controllable rounds for our bench session. Winchester’s X38SPD is an old-fashioned 158-grain lead wadcutter +P hollowpoint that we hoped would offer adequate stopping power with the least amount of blast. Not every .357 Magnum revolver will shoot .38 Special accurately, so we needed to see how these guns would respond. At only 110 grains, the Winchester (white box) hollowpoint number Q4204 is another old favorite with very good ratings in gelatin tests. Last, we tried a thoroughly modern cartridge, Federal’s 130-grain Hydra-Shok Personal Defense round (PD357HS2). Velocities were recorded separately from the bench session, firing offhand through an Oehler 35P chronograph. Standard procedure calls for five shots, but because pressure can vary from chamber to chamber, calculations of high/low and average velocities plus standard deviation were derived from six or seven shots respectively from each gun. Here’s how they fared.

Smith & Wesson M66, $545

The 66 is kin to the blued-steel Model 19 and the fixed-sight, longer-barreled (3 inches versus 2.5) Model 13. Even blindfolded we doubt anyone will prefer either the Taurus or Rossi products to the Smith & Wesson Model 66. The two-piece Uncle Mike’s grip offers the best handfit of the trio, we believe, and no one can deny the continuity of its double-action trigger.

The hammer spur is brief but wide. The cylinder latch protrudes from the frame and is checkered but will not interfere with a speedloader. The 66 offers a fully adjustable rear sight and a red ramp front sight pinned in place. The trigger is relieved on its underside, a feature we hadn’t noticed on prior models. This revolver’s stainless finish is flawless. As a result, the 66 weighs more and costs some $200 more than its rivals in this test.

In terms of performance, what do you get for more money? Consistency, not to mention comfort. It is our experience when comparing guns of different cost factors, the more expensive gun will outperform a less expensive gun over a wider range of circumstances. In terms of ammunition, the cheaper gun may well match the accuracy of a more expensive model with choice cartridges. For example, the Rossi was close in performance to the M66 with the two magnum cartridges. But it was unimpressive with the .38 Special round, wherein the bullet was asked to cope with the forcing cone after spending time in the unrifled chamber. The Smith & Wesson’s chambers and forcing cone simply did a better job of controlling the slug. We theorize that while the Rossi might shoot four out of 10 different rounds as well as the more costly M66, it would not shoot the remaining six cartridges nearly as well. Consistency is what we pay for.

For concealment purposes the K-frame is on the edge being too heavy. It weighs a full 36 ounces, but one saving grace is the cylinder is narrow and its frame is built to minimize height. Note how the bottom of the forcing cone is cut flat to make room for the cylinder rod. In extreme use this can compromise the durability of the forcing cone. The slightly larger L-frame series addresses this issue by making room for a full-diameter forcing cone, but the additional heft, overall height and cylinder diameter (approximately 1.45 vs.1.57 inches) can change the mission of this revolver.

We need to point out that the M66 ejector rod is short, and only a stiff jab will have a chance at reliably ejecting longer agnum cases. Loc-Tite was called for as the ejector rod loosened after only a few shots.

We would still prefer serration of the orange plastic insert on the front sight to absorb glare. Ours was uneven and sloppily applied, causing some distraction. The adjustable rear sight did not seem very cooperative in terms of elevation and would not adjust to any degree right of center. We think this is more than nitpicking. Perhaps Smith & Wesson is slacking off when its competitors should be attacking from all sides. If so, that’s a bad strategy, in our view.

Still, the M66 would be better suited as a primary gun than the either the Rossi or Taurus revolvers. We base this on its ability to handle the full-power magnum loads more comfortably and accurately.

Taurus 617, $355

Recently Taurus decided to drop its six-shot .357 and simply offer the extra round as a seven-shooter. On the surface, this seems perfectly reasonable.

But at the range, the Taurus 617 was lucky to get away with average groups of 3 inches at 15 yards. During dry firing, the action seemed to be smooth. Likewise when we fired the .38 Special loads. But when we fired the heavier magnum loads, we saw a plethora of bad side effects. First, the spent cases would stick in the cylinder and had to be pried loose. This usually occurs when the chambers are too large. Cartridge cases are designed to expand upon firing, but when this expansion is within the limits of a properly sized chamber, the case will then contract and eject easily. Another problem the Taurus had with the heavier loads resulted in jamming the trigger. It is our opinion that the force of ignition caused premature unlocking of the cylinder, putting the hand and ratchet out of phase. The action would then stutter while the hand tries to find its proper position. As a result we never knew what our double-action pull was going to feel like from shot to shot. Sometimes it was completely stuck or would suddenly stop and go. Other times it rushed forward. (We have seen a similar problem in titanium revolvers, wherein the gun had too little mass for the energy of the rounds expended.) Likely culprits for these malfunctions include the mainspring—a coil design prone to stacking. Coil springs are also less consistent than leaf springs such as those used in the K-, L- and N-frame Smith & Wesson revolvers. Another reason for the uneven trigger pull could be poorly machined parts that shift or rub up against improperly finished surfaces.

The 617 may resemble the smaller 85 series, but it weighs almost half a pound more. The extra weight is in the grip, where more room is needed for a longer, more powerful mainspring, and also in the frame, which is longer from the breech to the backstrap. This additional length changes the orientation of the hand to the trigger, and some of our staffers felt the grip was uncomfortable.

Because of the malfunctions and the grip discomfort we felt when shooting the 617, it is our opinion that most magnum loads are too much for this gun. It would be more reliable handling the current crop of .38 Special +P loads instead.

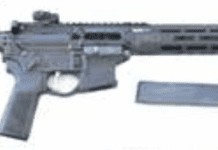

Rossi 461, $298

On the basis of our experience with the Rossi 461, this marque re-enters the market primarily where it left off with a basic, less expensive, if not older design. While Taurus seems to produce guns with innovative ideas, the company seems to be having trouble in the execution of some really useful ideas. Rossi, on the other hand, seems content to offer little variation on proven design.

For one, the 461 is the only revolver in the test (and among the few still on the market at all) that use a nose pin mounted directly on the hammer to reach through the breech face. Frankly, we prefer this to the inertial firing pin floating inside the frame waiting for a “croquet” or “combination” shot. We prefer it because it is so much easier to refine the trigger on this older design. This offers the competition gunsmith the option of lowering mainspring pressure (and trigger pull weight) by simply shaving the nose pin so it can move further through the breech.

As we noted before, careful ammo selection can yield good results with low-cost guns, as proven out when the Rossi outshot the Smith & Wesson 66 firing the 110-grain hollowpoints. Also helpful, the 461 is more concealable than the M66 and much cheaper. Its hammer could be bobbed for snag-free concealment, and the loss of mass at the hammer could be made up for with the narrowed pin so that the same energy is delivered via increased distance and hammer velocity.

The grip is far more comfortable to hold than it is to shoot with; we need more material at the top of the back strap, please. The frame is nearly as small as the little Taurus 85s. Will it hold up? Probably, if you stick to lighter slugs such as the Winchester 110-grain hollowpoints.

We liked the arcing sight picture rather than trying to reconcile a notch straight across. When we started, the ejector star was stubborn about resettling over its location pegs (another “ancient” design). The 461 got over this and we think it will continue to improve as other parts break in.

Don’t get us wrong, we think the Smith & Wesson 66 is the best gun here, but Rossi’s 461 is a very useful little tool.

Gun Tests Recommends

Smith & Wesson 66, $545. Buy It. Even with the small problems we encountered, this is a superior weapon, and few revolvers can match this incarnation of the snubnosed K-frame.

Taurus 617, $355. Don’t Buy. We wouldn’t feel comfortable shooting anything stouter than .38 +P ammunition in this gun, which spoils its mission as a .357 Magnum, in our view.

Rossi 461, $298. Conditional Buy. Not your everyday shooter, but an “ace in the hole” weapon at a bargain price.