There are a handful of shooting opportunities left in which most hunters would gladly trade putting less shot in the air if it meant less pounding on their shoulders. Two such situations would include Mexican or South American duck or dove hunting. Besides this extreme, there are other locales and wingshooting where hunters don’t necessarily need to launch the payload of a 12 gauge. A 20 gauge will easily dispatch fluttering New Jersey woodcock or shy Texas rails, and most hunters are happy not to tote the bigger receivers and thicker barrels most 12 gauges wear. A lighter weight, more nimble 20 is plenty.

We recently tested a trio of 20 gauge autoloading shotguns to see which one we would buy instead of a new recliner, because that’s roughly the cost trade-off you’re looking at. Remington’s 11-87 Premier MSRPs for around $756, and we’ve seen them selling for $600. Like the Beretta and Browning guns, it had a 3-inch chamber and 28-inch barrel. However, its receiver was steel, which contributed to its heavier 7.4-pound weight. The Browning Gold Hunter Classic 20 gauge came in at 7.1 pounds, despite an alloy receiver, and was priced at $894 MSRP. The Classic is distinguished from the Gold Hunter by the former’s humpbacked receiver, reminiscent of the Browning Auto 5, thus the name Classic. We’ve seen the gun sell for as low as $650, but it’s available only at Browning’s Full-Line and Medallion dealers. Last up was the 20-gauge incarnation of the Beretta AL391 Urika autoloader, which supplanted the AL390 in 2000. It is more expensive than the others at $960 MSRP, and we’ve regularly seen the guns selling at retail for $800 and up. What do you get for your money? Here’s what we found:

How We Tested

We acquired three hunting loads and one range load to shoot in this test, mixing lengths, powder charges, and shot charges during the test. Most notably, we never had a hiccup with any of the guns in terms of operation. They fed our 2.75-inch and 3-inch loads interchangeably, and loaded and extracted all the shells perfectly.

Our test rounds were Sellier & Bellot’s 2.75-inch Field Load, whose shot cup was filled with 1 ounce of No. 8s pushed by a powder charge of 2.75 dr. eq. Also included was a 2.75-inch Federal Hi-Power Load (No. 7 1/2s, 2.75 dr. eq., 1 ounce of shot), and a 3-inch shotshell, Winchester’s Supreme Double X Magnum, which we shot loaded with No. 6s, 3 dr. eq., and 1.25 ounces of shot. For most of our range shooting, we used 2.75-inch Winchester AA208 Target Loads, with 7/8-ounce of No. 8s pushed by a 2.5 dr. eq. powder charge.

[PDFCAP(1)]We conducted the test in three segments, two of which were fun. The unfun segment was counting hundreds of little holes in paper during the patterning test. All the guns came with interchangeable chokes, so in some respects it’s not all that helpful to compare how they pattern, since the charge density can be adjusted with the flick of a choke wrench. Still, we patterned all three loads in all three guns using what we thought would be the most useful choke (Modified, in this case) for most applications of the gun, including steel shot, and we did check the guns’ points of aim. In the patterning test, we used a Hunter John shotgun patterning target, shooting the rounds into the target’s 30-inch circle at 40 yards. We counted the number of pellets in a given shell and used that number to divide into the number of hits in the circle, which produced a pattern efficiency percentage reported in the accompanying table. Also, as we examined the patterns, we looked for clumping or open areas in the pattern.

More fun were the five-stand and field-testing segments. For our purposes, it’s best to shoot these guns side by side in a range of target presentations, which we did at American Shooting Centers in Houston. That gave us a real feel of how the guns handled shot to shot. It also gave us insights into how the guns mounted on different targets, though the Beretta’s fully adjustable stock removed any doubt about which gun had the most flexibility. For field shooting purposes, we did a little dove hunting with the guns, but, frankly, that’s an uneven playing field. We can’t control when the birds fly or from what angle, so it’s difficult to compare the guns fairly. Also, it’s a pain in the butt to swap three shotguns around in the field with any regularity. However, we persevered and used them to collect a few mourning doves for dinner.

Of course, during all this shooting we formed opinions about what we liked and didn’t like about each gun. These opinions are duly noted below for your information and entertainment.

Beretta Urika AL391 20 Gauge, $960

We tested the 12 gauge version of this gun in July 2000. At the time, we were underwhelmed with the 391, which was supposed to replace the AL390 Silver Mallard we had lauded on many occasions. We gave the 12 gauge a Conditional Buy rating at the time, saying we didn’t think the Urika was so much better than the Silver Mallards that we would rush out and buy one of the new guns.

Naturally, this didn’t make us many friends in Accokeek, Maryland, where Beretta is based. The company was pushing the Urika introduction hard, and we were a sharp rock in their promotional shoe. But absence does indeed make the heart grow fonder. As the supply of 390s dried up, we were forced to evaluate the 391 solely against guns from other companies, and we find it stacks up quite nicely from the get-go.

The Urikas ship in molded plastic cases that we would consider buying for other guns (if they fit). Inside the case was the gun, a one-round magazine reducer plug, a spare recoil pad, stock drop and cast spacers, a grip cap, stock swivels, gun oil, valve hook wrenches, five choke tubes, and a tube wrench.

Likewise, the gun is full of features. Naturally, the gas system is self compensating and self cleaning. The system is touted to handle shells as light as 7/8 ounces to 2 ounces without adjustment, and using our test rounds, we verified that the gun had no trouble adapting to different powder charges. A recoil dampener in the back of the action reduces the impact of the breech bolt on the receiver, which made the gun shoot softer than we expected, given its light weight. A detachable trigger assembly popped out fairly easily. The trigger guard was opened wide enough to insert a gloved finger in it without firing the gun. A cut-off on the left side of the receiver allows the action to be opened and kept open while the chambered shell is extracted. This is handy both for safety or for changing shotshells on the fly, such as when ducks and geese are intermingled. The cross-bolt safety in front of the trigger guard is adaptable for lefties or righties.

On the shoulder, the gun offers other choices. The stock comes with two buttpads, one hard plastic and the other rubber. The rubber pad offers a softer shooting surface and a slightly longer length of pull. Moreover, there are stock cast and drop spacers, which we used to make the stock fit better. This gave the Beretta a big advantage over the other two guns.

But do these features make this gun worth the extra money? In our view, yes. For many shooters, the case, choke tubes, swivels and other extras alone will make up the price difference. If you don’t want or need those things, of course, that’s another story.

The gun’s barrel was blued steel, and the alloy receiver had contrasting matte and glossy finishes. The semi-gloss finish on the walnut stock showed off the gun’s nice buttstock grain, and the finish was smooth and consistent. The gun as we shot it weighed only 6.1 pounds. It had a 28-inch barrel and a 48-inch overall length, with a 14.25-inch length of pull with the plastic buttplate. We wound up adding cast-on to the stock to make the gun point better, but the 1.4-inch drop at comb and 2.1-inch drop at heel measurements were very close to factory settings. The trigger broke at 5.6 pounds. The barrels are hard-chromed and very easy to clean.

Loading and unloading the gun was uneventful. The easiest way to charge the gun is to turn it on its left side and drop a round into the chamber, then use the breech bolt release button to free the action forward. Then load up to two rounds in the magazine. If you want to use the cut-off, you engage the switch and open the action. This prevents the action from closing or rounds being inserted in the magazine. But watch your fingers when the bolt slams home.

At the range and in the field, the Urika was a joy to carry and handle. The forend is only 1.6 inches thick, and the receiver body is 1.4 inches thick. After the stock was adjusted, the gun came to the face smoothly and easily, and the patterning targets showed that it shot where it was aimed, meaning the pitch down of the stock (3.5 inches) allowed the shooter’s eye to see the top of the sighting plane properly. Of course, it could have been changed if necessary. The 6mm ventilated rib had a crosshatch pattern on its top side to reduce glare, and we found the visual transition from the receiver to the rib to be seamless. A single, small gold sighting bead adorned the muzzle end of the rib. We thought the bead tended to force the focus of the hunter’s eye to the front of the gun instead of to the target, so if we owned the Urika, we might remove it. Checkering on the grip and forend afforded a solid grasp of the gun, but as we noted on the 12 gauge Urika, the shape of the pistol grip takes some getting used to. In fact, we thought the Remington’s grip felt the best. Though the pull weight of the trigger wasn’t excessive at 5.6 pounds, it was mushy and uncertain.

We patterned the gun with its Modified tube, shooting three rounds per load into a Hunter John target. The Winchester Magnum No. 6s shot 60 percent patterns, followed by the Sellier & Bellot No. 8s and Federal Hi-Power No. 7 1/2s at 54 percent each. That’s right at the densities we would expect for a Modified choke. Reading the location of the three-shot patterns, it seemed the shot shifted to the left on all the targets. We estimate the gun was shooting about 2 inches to the left with its Modified choke. We didn’t notice any clumping or open areas, except that the core pattern (in about a 20-inch ring) was denser than we expected.

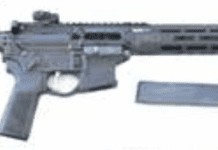

Browning Gold Hunter Classic 20 gauge, $894

Like the Urika, we have not previously reviewed the 20 gauge version of this gun, though we looked at the similar 20-gauge Gold Hunter in November 1999 and the plastic Classic Stalker 12 gauge in August 2000. Both times we gave the Browning a Buy It rating, though we didn’t like the glossy stock of the Gold Hunter 20 gauge.

The Gold Hunter Classic itself lacked the extras Beretta offered in some crucial areas. The company’s new Fusion package more directly competes with the Urikas, we believe, in that the Browning Fusions are 8 ounces lighter than the Hunters, include a gun case similar to the Urika’s, and include gun oil, a Hi-Viz Pro-Comp fiber-optic sight with a selection of light pipes, five choke tubes ranging from Skeet to Full, and stock drop and cast adjustments. Sound familiar?

However, we have yet to see a Fusion being sold at retail, and the Classic is available. We tested the 28-inch model, which comes with Full, Modified, and I.C. chokes and chambers rounds up to 3 inches long. It features a semi-humpback design and a magazine cut-off, which works like the Beretta’s described above. Browning says the Classic also has an adjustable stock that allows comb adjustment over a 1/4-inch range (1/8 inch up and 1/8 inch down), but the gun pointed well out of the box for us, so we didn’t explore this option.

The Browning Gold shotgun is a gas-operated, semi-automatic shotgun capable of shooting five shots (with the magazine plug removed using 2.75-inch loads) in rapid succession with each pull of the trigger. Upon firing, high-pressure gas from behind the shot charge passes through two ports in the barrel, through the gas bracket and into the gas cylinder. High-pressure gases force the gas piston rearward, applying pressure to the piston rod. As the piston rod moves rearward, it pushes the bolt assembly rearward, operating the action. As the bolt assembly moves rearward, it recocks the hammer, and ejects the fired shell.

After full rearward travel, the bolt assembly returns forward, picking up a new shell from the magazine and chambering it automatically. After the last shell is fired, the bolt assembly locks to the rear, instead of returning forward. The Gold shotgun is delivered with the magazine adapter in the magazine, which limits the gun to three shots, in accordance with federal migratory bird laws. If you do not want your gun to be limited, merely take out the three-shot adapter as explained in the owner’s manual under “Three-Shot Adapter.”

The crossbolt-type safety prevents the trigger from being pulled when in the “on safe” position. The safety is located at the rear of the trigger guard In the “off safe” position, a red warning band is visible on the safety button on the left side of the trigger guard. To make the gun on safe, press the safety button to the right. To move the safety button to the Fire position, press the safety to the left. The safety is reversible by a competent gunsmith.

The Gold shotgun is delivered, in the box, with the barrel removed and the forearm still attached to the magazine tube. Assembling the gun is uneventful for anyone who has put together a semiauto, but you do have to be careful not to squeeze too hard on the open rear end of the forearm. Too much pressure could cause the wood to split.

Disassembly is likewise straightforward, except that after the barrel has been removed from your gun, leave the bolt in the open position. Do not press the carrier release button. If the bolt is released forward with the barrel removed, the cartridge stop will hit the front of the receiver and cause damage. Also, the trigger group or bolt can be removed if the action becomes excessively dirty or wet.

There are two methods for getting a loaded shell into the chamber of the Gold shotgun. One is to load the chamber through the ejection port, as on the Beretta and Remington guns. The other is to load the chamber manually from the magazine using Browning’s “Speed Loading” feature. With the bolt open, insert a shell into the magazine. The shell will be automatically cycled from the magazine to the chamber, so keep your fingers clear of the ejection port. Then you load the magazine to full capacity.

To unload the Gold shotgun, grasp the operating handle and cycle the action until all rounds are ejected.

The 20-gauge Gold shotgun’s barrel is threaded to accept the Browning Standard Invector chokes. The degree of choke is indicated twice on each choke tube: Inscribed on the side of the tube, and indicated with a “notch” code on the top rim of the tube. Browning 20 gauge Standard Invector choke tubes are made with tempered steel and are compatible with magnum lead and steel shot loads and rifled slug loads. Browning’s universal tube wrench is used to remove and install these tubes. Before installing a tube, check the internal choke tube threads in the muzzle, as well as the threads on the Invector choke tube to be sure they are clean. Lightly oil the threads.

Our Browning had a satin gloss finish we preferred to the high-gloss version we had tested previously. It had a half-inch-thick rubber buttpad that cushioned recoil, but the top of the pad needed to be ground down for better mounting, in our view. The stock grain was straight, and the finish allowed it to present well, we thought. The checkering was sharp on the grip and forend, though we would have liked the checkering to come back toward the rear of the forend another inch or so.

The gun as we shot it weighed 7.1 pounds. It had a 28-inch barrel and a 48.25-inch overall length, with a 14.25-inch length of pull. The 1.75-inch drop at comb and 2.0-inch drop at heel measurements were fine for most shooters. The trigger broke at 6.75 pounds and needed work to remove creep and backlash. Overall, we liked how the Browning handled, though it was slower to target than the Beretta, in our view. The gun was just bigger overall, measuring 1.9 inches thick at the forearm and 1.3 inches thick at the grip. The receiver body was 1.4 inches thick, the same as the Beretta’s. Still, the gun came to the face smoothly and easily, and it shot where it was aimed, though it had less pitch down (2.6 inches) in its stock. The 0.25-inch ventilated rib was textured to reduce glare, and we easily saw the target down the receiver and the rib. A single white sighting bead terminated the sighting plane at the muzzle.

In this gun’s Modified tube, the Winchester Magnum No. 6s shot 57 percent patterns, followed by the Sellier & Bellot No. 8s at 52 percent. The Federal Hi-Power No. 7 1/2s dispersed into a 40 percent pattern, much less than we would expect for the choke. The other two were near what we would expect a Modified choke to deliver. The shot pattern was high and to the left on all the targets.

Remington 11-87 Premier 20-Gauge No. 9591, $756

Duplicating its 12-gauge big brother, the Model 11-87 Premier 20-gauge is built on a scaled down, small-frame receiver. The company’s website says the gun is lighter weight and faster handling than the 12 gauge, and to some extent that’s true, since the 12 gauge goes 7.75 pounds. But Remington says the 20’s average weight is just under 7 pounds, but our sample went 7.4 pounds.

The 20-gauge version features an American walnut stock with a high-gloss finish, sharp-cut checkering on stock and forend, and a rubber recoil pad. The barrel has a highly polished blued finish, and the receiver is replete with fine-line engraving. Both 26-inch or 28-inch vent rib barrels are available, and they include an ivory front bead and metal mid-bead, and both are fitted with the Rem Choke system. The magazine holds four shells, but a provided plug can limit the gun’s capacity to three. Our sample with a 28-inch barrel measured 48.25 inches in length.

Unlike the Beretta, the Remington ships in a cardboard box and comes with minimal accessories, including three chokes (Full, Modified, and IC), a choke wrench, and two suppository-looking green-plastic shells. What, pray tell, were these?

The owner’s manual said they were keys to unlock the gun’s trigger mechanism. By pulling apart two halves of the shell, a metal slotted strip was exposed, and the strip fit into a J-shaped slot behind the trigger guard. Turning the key in the slot allowed the trigger block to rotate and unengage. The system worked very well, and we didn’t have any instances of the block inadvertently engaging.

The gun easily adapted to different powder charges, and we had no feeding problems. The plastic trigger guard opening wasn’t quite as wide (0.95 inch top to bottom) as the Beretta (1.1 inch). This gun lacked a cut-off switch. The Remington soft rubber buttpad felt good on the shoulder, but like the Browning, its top edge needed to be broken.

The glossy finish showed off the straight walnut grain, which made the gun look nice but which isn’t the best choice for hunting, in our view. The Remington’s wood was more golden in tint, while the Browning was reddish and the Beretta chocolate toned. The gun had a 14-inch length of pull, a 1.4-inch drop at comb and 2.1-inch drop at heel, very similar to the Gold Hunter. The trigger broke at 5 pounds very cleanly. The trigger itself was thinner than the others and felt better to the finger. The gun loaded similarly to the Beretta, in that dropping a round into the chamber then using the breech bolt release button under the magazine to release the bolt. Inconveniently, the gun comes unplugged, so you’ll need to install the supplied plastic plug to conform to the migratory bird laws. With the plug in, two rounds fit in the magazine.

The Premier’s forend was 1.9 inches thick, and the receiver was the thinnest in the test at 1.3 inches. The Premier’s stock wasn’t adjustable, but it came up and pointed well. It had pitch down of 3.25 inches. The 0.30-inch-wide ventilated rib had a lengthwise pattern to reduce glare. Checkering on the grip and forend were well cut, and we liked the pistol grip’s angle to the trigger better than the Beretta’s.

In the Premier, the Winchester Magnum No. 6s developed 70 percent patterns. Sellier & Bellot No. 8s hit 60 percent of their shot inside the 30-inch circle at 40 yards, and Federal Hi-Power No. 7 1/2s 62 percent. Basically, this is Improved Modified or Full Choke performance. Also, we estimate the gun shot about 3 inches low.

Gun Tests Recommends

Beretta Urika AL391 20 Gauge, $960. Buy It. The accessories alone set this gun apart. But it’s also lightweight, good looking, and fast. A stocking dealer/gun range operator for both Beretta and Browning says he sees a lot of the Urikas in competition (and fewer Brownings and nearly no Remingtons), and his rental gun business has shown the Berettas need repair about one quarter as often as his Brownings. With all the gun has going for it, it would be our first pick in this test.

Browning Gold Hunter Classic 20 gauge 011-115604, $894. Conditional Buy. Nothing wrong here. If the Beretta’s accessories aren’t for you, this is still a capable, good looking shotgun. The range operator mentioned above said that despite what other people shoot, he likes the Brownings better. And he noted that for lower volume shooters, the Browning’s repair needs won’t be that bothersome.

Remington 11-87 Premier 20-Gauge No. 9591, $756. Conditional Buy. Like the Browning above, there’s a lot to like here. This gun had a nice trigger, it swung well, and looked nice, even if some of that gloss isn’t a good choice on a hunting gun, in our view. We preferred its grip to the Browning and Beretta. However, it was a little heavier than the others. If you get a chance to shoulder all three guns and prefer the Remington, we think you could buy it and be satisfied.