Barrel length has always been a clue to the intended use and function of a revolver. Self-defense models usually sport barrel lengths of 3 inches or less for purposes of concealment, increased maneuverability in tight spaces, and to discourage an assailant from grabbing it in extreme cases.

In contrast, target and hunting revolvers traditionally sport longer barrels. Keeping the bullet in front of expanding gases adds velocity without the use of additional powder. Also, when weight up front is increased, recoil is reduced. The longer barrel also moves the front sight blade farther from the shooter’s eyes, increasing sight radius and improving targeting. Finally, the longer barrel is easier to use with a support in the field.

In this test we look at battery mates to the rimfire target, silhouette, and hunting revolvers tested in the September 2001 issue of Gun Tests chambered for .357 Magnum. The longer magnum case is bolstered for higher pressure and widely recognized as the minimum caliber for hunting medium sized game such as pigs and in some cases even deer. To satisfy this market, Taurus has recently released its $461 Silhouette Series revolvers with 12-inch barrels chambered not only for .357 Magnum but .22 Long Rifle (LR) and Winchester Magnum Rifle (WMR) as well. Here we match the new Taurus with entries from Sturm, Ruger & Co., and Smith & Wesson. The longest Ruger New Model Blackhawk, $505, is a 6.5-inch model popular among Cowboy Action enthusiasts, but we wanted to see if it was a worthy mid-distance revolver in its own right. And from Smith & Wesson, the longest available is a full-lug 8 3/8-inch barrel on a medium-large (L)-framed 686, $550. With this trio in hand we headed for the range to discover the longs and shorts of each revolver.

Range Session

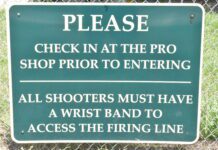

Even with the longer sight radius and obvious design intent of at least two of our players, we chose to test at 25 yards rather than 50 yards. It is our experience that firing an open-sighted handgun at targets beyond 25 yards more likely reflects the ability of the shooter than the accuracy of the gun. Had we used a machine rest we would have been tempted to list data from a longer distance, but instead each gun was fired from a sandbag rest. Our test procedure was aided by the acquisition of a new product on the market that integrated very well with our bench setup. The Standbag, $26.95, from Aimright in San Antonio, (210) 661-4356 or www.thestandbag.com, is a saddlebag-style design that will stabilize a pistol barrel or rifle fore-end on the edge of a 2 by 4 or similar object. Data was primarily collected during single-action-only fire, but we did measure groups fired double action for context. Chronograph (velocity) information was collected by using an Oehler 35P printer model. In fact, despite being hit by friendly fire during the rimfire revolver test (September 2001), our Oehler is still functioning because the computer mechanism is separate from the screens that stand downrange.

We chose three very different cartridges for our tests. The hottest load was the 125-grain .357 Magnum from Black Hills Ammunition, (605) 348-5150. From PMC, (702) 294-0025, we chose another magnum cartridge, but one designed for self-defense (lower recoil and more expansion) with a slug weighing 150 grains. Then, we tried a .38 Special target load that featured a fresh Winchester brass case, 3.1 grains of Accurate Arms Solo 1000 and the Star Manufacturing lead hollow-based 148-grain wadcutter. This is the same load used by pistolsmith Fred Craig to win the Stock Gun title at the 1999 NRA National Action Pistol Championship Bianchi Cup in an 8 3/8-inch-long Smith & Wesson 686. Armed with this variety of ammunition, we felt confident our shooting would accurately diagnose the characteristics of each gun.

Ruger New Model Blackhawk, $505

The New Model Blackhawk was one handsome piece of stainless steel. Fit and finish was exceptional. This model, KBN 36, is a single-action-only revolver, which is the preferred mode of fire for most hunting and silhouette competition. Many consider this gun to be an updated “cowboy” gun with advanced metallurgy, adjustable sights and added safety features. On such feature is the loading gate that alone disables the firing mechanism and allows for the Blackhawk to be reloaded or emptied without pulling the hammer back. Complementing the click adjustable (for both windage and elevation) rear sight is a bold, serrated front ramp that is raised from the barrel by a stanchion and pinned into place. A word about the windage (right and left) adjustment; Contrary to most systems you turn the adjustment screw left to move the point of impact (POI) to the right and vice, versa. Another function you may view as “south of the equator” is that the cylinder rotates clockwise when the hammer is pulled back, a feature common to Colt’s. While the rimfire Blackhawks come with separate cylinders for .22 LR and .22 WMR, but no such accommodation is made for .38 Special and .357 Magnum. Rimfire revolvers chambered for the magnum cartridge will fire its shorter Long Rifle brother, but build up of debris in a rimfire chamber is more dangerous than in the centerfire combination. The edge of a rimfire cartridge is live, and if it does not seat fully into the chamber it is actually possible to ignite the round as the cylinder is closed or as it strikes the breechface during rotation.

The best practice is to clean the cylinders between loads, especially when changing from lead to jacketed ammunition. The cylinder of the Blackhawk is easily removed by pushing the base pin latch on the left side of the frame and pulling forward the base pin, which is the axle upon which the cylinder turns. Opening the loading gate allows the cylinder to the exit from the left. Ejection of round is one at a time and without a click or other key to indexing, you have to time the alignment of the chambers with the open gate and use the ejector rod to flush out empty brass. The same goes for loading. To load one round and line it up for fire, rotate the cylinder clockwise four clicks and then close the gate. Pulling back the hammer will bring the fresh round in front of the firing pin hole. A firing pin block separates the primer from the firing pin until the trigger is pressed.

At 6.5 inches the Ruger not only had the shortest barrel, but due to its ejection system only some 1.8 inches of barrel was free to rest on the Standbag. Yes, we did end up supporting the gun further back but this was not ideal because the ejector housing is offset to the right underneath the barrel. We felt that without a smooth symmetrical surface underneath the barrel, our use of the bench rest was to some degree compromised.

Real world ergonomics are also a critical element and grip profile, especially in this Old West design is worth mentioning. The design of the grip on the Blackhawk is perhaps the most recoil friendly because the gun may be allowed to ride up in the hand and dissipate recoil. However, you have to be careful that this does not happen prematurely and add height to the point of impact. But with the Ruger’s consistent, short trigger we were able to be consistent with our grip as well.

In terms of accuracy, the Ruger delivered averages of 1.4-, 1.5-, and 1.6-inch five-shot groups with the 125-, 150-, and 148-grain rounds respectively. In fact there was very little difference in group-size throughout, no matter how many groups we shot or what ammunition we used. It also showed the least variation in performance between the magnum and .38 Special rounds. Standard deviation, the difference between highest and lowest velocity as expressed on a bell curve, was also far lower when firing the light, .38 Special target load than its competitors. This means that machining of each chamber is tight, consistent in relative volume, and efficient.

Smith & Wesson 686-5, $550

In 1999 the NRA was in its second year of awarding a Stock Gun title at the National Action Pistol Championship Bianchi Cup in Columbia, Missouri. Chad Dietrich had won the inaugural Stock Gun title, and 1999 was Fred Craig’s turn to win. He did so with a revolver very much like the one tested here. Six-shot capacity, factory sights and perhaps only an action job. The Bianchi Cup is a double-action game, and the Smith & Wesson mechanism with a single solid mainspring has dominated the wheelgun entries.

The “dash-five” model 686 features an 83/8-inch barrel with full underlug and shrouded ejector rod. The sights on this model include a serrated ramp with orange insert up front and an adjustable assembly that has been around for years. Outside of the white outline on the rear blade it is the same machine that was adapted years ago by pistolsmith Armand Swenson for use on the 1911 Government model pistol predating the Bo-Mar system. The only new features since its introduction are the Hogue rubber Monogrip, the use of MIM parts inside, and bold graphics on the right side of the barrel. The 686-5 is ideally suited for supported fire. The long underside of the barrel is broad and uninterrupted as well as being extra long.

Standing unsupported, we found the 686-5 to be well balanced despite its mass. This is likely due to the backless grip (a Hogue model, [800] GET GRIP) and how it takes advantage of the frame for the highest hold possible. Another element is the sight radius. We found the 10.1-inch sight radius to be ideal. We had a clear look at the front sight, easy definition of the light bars surrounding it, and enough vision left over to truly define the distant target. All this added up to sub 1-inch groups measuring as little as 0.5 inches. But let’s talk about a fly in the ointment, one that likes to land in the mix of every revolver made. Accuracy data was collected by the measuring of groups fired from five of the six chambers loaded at random. Luck was with the 686-5 over the short term but in firing additional groups we were consistently able to measure even better five-shot groups after firing a sixth time. Now, most of the 6-shot groups measured 1.1 to 1.2 inches, so, we’re getting critical from the top of the pyramid down. The fact is that revolvers are multiple short-barreled rifles rolled into one gun. While the inside volume of the barrel remains the same, the inside dimensions of each chamber tends to vary a little. Since we kept having one-holed groups spoiled by a flyer, we went looking for the answer. Our first stop was the chronograph. Among each of the six shots of 125-grain .357 Magnum JHP rounds fired through the chronograph, one shot was clearly traveling at a much greater rate of speed. In computing five of the six shots, we read a high and low of 1,590 and 1,554 fps respectively for an average of 1,575 fps. The remaining shot traveled at 1,645 fps. This equates to a higher print on the target.

Firing the 150-grain PMC rounds, the high and low was as much as 100 fps apart. Firing our handload created a five-shot average speed of 873 fps with the maverick speeder at 908 fps. The key to consistently shooting a seamless group then, is to isolate the tight chamber and not use it or simply to fire using one chamber at a time. In our 686-5 we consistently saw two pairs of chambers fire nearly the same velocity, one fire a little lower and the other much higher. Even with this problem, the Smith was very accurate, and we wound up preferring it despite this flaw.

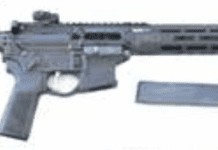

Taurus M66 12-Inch .357 Magnum, $461

Taurus International Manufacturing Incorporated (T.I.M.I.) has made a lot of waves in recent years with big guns. The 454 Casull Raging Bull set the stage for a new era of large-framed revolvers not by inventing a new caliber but by making such guns practical and appealing to a wider audience. However, the 12-inch barreled revolver here is, like the Smith & Wesson 686, based on the company’s medium frame. The kicker is that it is chambered for an extra round. Everybody wants to know if Taurus is (1) grandstanding or (2) trying to set a new standard with the slew of seven-shot revolvers in the company’s catalog. In view of current round counts in semi-autos, we feel it is the latter.

One of the more interesting aspects of our testing of the Model 66 arises out of the Accuracy & Chronograph data. First, notice that the M66 produced the most velocity by 80 to 90 fps over its rivals when firing the hot Black Hills 125-grain JHP round. (Please note from the driver’s seat that recoil with this round was arguably the lowest among all three revolvers.)

Now look at the group sizes. The Taurus fired the magnum rounds on par with the Ruger. Firing the light .38 Special load, accuracy noticeably drops off. The reason being when the shorter Special rounds are loaded, the slug sits back in the chamber farther from the taper of the chamber and farther away from the forcing cone. The bullet spends more time in an unrifled space. In this case the hollow-based wadcutter (HBWC) is seated deeply into the case, and offering even less support and creating more distance from the rifling. This creates variations in pressure, thus velocity, thus accuracy. In short, we feel this gun is best suited for full-length .357 Magnum rounds of hot loads. It virtually eats them up, making this revolver a ball to shoot.

To make the hammer drop, the Smith & Wesson revolvers use a single leaf torsion bar and the Rugers use a similar, slightly more complicated, system. The Taurus revolvers use a single coil spring much like the one found in the smaller Smith & Wesson J-frame revolvers. When the spring is short, it is easy to maintain enough energy for a hard strike without too much stacking, the increase of resistance the shooter feels against the trigger. Lengthen this spring and stacking is increased. While the trigger on the Taurus M66 was smooth and soft, we would have opted for a heavier spring. Firing single action only, wherein the hammer is set so far back it can pack an adequate wallop, we had no malfunctions. Firing double action, however, the shorter stroke was enough to cause misfires. This has been our observation on more than one occasion in the case of Taurus revolvers.

We feel it is about time Taurus took a look at current coil-spring technology and solve this problem. In terms of recoil springs in small semi-autos, for example, advancements have been made so that the vast majority of these guns are 100 percent reliable. Thanks to progressive winding, flat wire and multi-filament springs, we don’t even hear much about “limp wristing” anymore. Taurus continues to aggressively market refreshing new designs, but the next advertisement from T.I.M.I. we’d like to see would feature words about an “improved” mainspring design.

Gun Tests Recommends

Ruger New Model Blackhawk, $505. Buy It. Even though the KBN36 is limited to single action, its versatility is exceptional. First- rate construction makes it a showpiece for Cowboy Acton or a potential winner in silhouette.

Smith & Wesson 686-5, $550. Buy It. This model is not widely advertised, and it is not marketed as a special match-grade edition. But we found it set an extremely high standard. It is simply one of the best production guns you can buy, and it’s our first pick in this test.

Taurus M66 SS KL, $461. Conditional Buy. Its one major flaw, a weak recoil spring, is easily fixed, but Taurus should upgrade this part. Otherwise, there is some untapped potential here, and you can have a lot of fun with this gun.

Also With This Article

[PDFCAP(5)]