John Cantius Garand (1888-1974) was a French-Canadian machine designer who lived in New York. Gen. Julian Hatcher, in his famous and fine reference book, “Hatcher’s Notebook,” tells us that his close friend John Garand pronounced his name with the accent on the first syllable, to rhyme with the word “parent.” So his rifles are GARands, not gaRANDS.

Around the time of WWI, John Garand came up with a primer-driven, fully automatic rifle that got the attention of U.S. military “brass.” However, a change in powder type used within the cartridge led Garand to abandon that design for one which was gas driven, and which evolved into the well-known M1 Garand. The first “production” Garands (after their acceptance) used a muzzle-cap device to trap and redirect the gas, but this was soon changed to a now-conventional hole in the barrel as the gas port.

In 1929 there was a competition at Aberdeen Proving Ground to pick the new U.S. official rifle, and the Garand — in the supposed new military caliber of .276 Pedersen — came out on top. It was then a ten-shot rifle. When the Garand rifle was submitted to the Army, then-Chief-of-Staff Gen. MacArthur informed the designers there was to be no change in the official U.S. cartridge to .276. The .30-’06 would be retained, and all the development work on the new, now-rejected, cartridge, at taxpayer expense, was wasted.

Garand, however, had been working with the .30-’06 cartridge all along, and when the new trials came for .30-caliber rifles, his revised eight-shot design was the winner. In 1936 it was officially designated the “U.S. Rifle Cal. .30 M1.” Production of the M1 Garand began at Springfield Armory (not the same place that has that name today) in January 1937, with the first rifles being delivered in August. During WWII, a total of over four million Garands were produced, most by Springfield Armory, and many by Winchester. The rifles ultimately saw service in three wars, including Korea and Viet Nam.

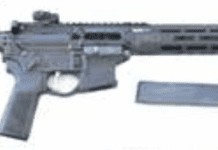

In this report we look at four examples of Garand’s rifle, one by the new Springfield Armory in Geneseo, IL ($1,061), one by International Harvester obtained through the Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP, $550), a third from Lithgow Arsenal in Australia ($750), and a gun-show-special Korean War relic from the original Springfield Armory ($450).

They all had full-length wood stocks, a few stamped parts, excellent machining on all the metal work, adjustable sights featuring an aperture rear and protected front post, and all used the eight-shot, en-bloc clip that has been so reliable for so long. Long years ago we saw for sale surplus .30-’06 ammunition loaded into the eight-shot clips and shipped in military-style ammunition cans. Today’s Garand shooter will have to load the clips himself, which is easy.

The Garand mechanism is a bit odd if you’ve never experienced it. Pulling back on the bolt handle on an unloaded rifle causes the bolt to lock open. On the insertion of the loaded clip the bolt flies forward, strips off the top round and chambers it. The bolt will also strip off part of your thumb if you’re not careful, leading to the infamous “Garand thumb.” None of our shooters had that problem, we’re proud to announce.

After the firing of all eight shots, the bolt stays open and the clip flies out with a loud “ping,” leaving the rifle ready for the next eight rounds. There are two-shot clips available for match shooters, who need to fire ten shots in a string. Many other accessories are available for Garand owners, including surplus items that also work on the M14. These include slings, bore and chamber brushes, original cleaning solvents, etc.

One accessory we had on hand, but ran out of time to try, was an insert to permit the .30-’06 Garand to chamber and fire .308 Winchester ammo. This fit into the chamber and stayed in place until removed with a broken-case extractor. For more information on the conversion units ($25), log on to www.armscorpusa.com/Products/m1_garand_parts.htm.

All the bores of the four rifles appeared very good at first glance. All the rifles were conglomerates of the parts of various makers, even the “new” Springfield Armory rifle. The metal parts and stock wood had varying degrees of distress, from none to God-awful. All the rifles had mil-spec adjustable rear sights, all with the same-diameter aperture, and with the windage knob on the left and elevation on the right. With one slight exception, noted below, all the sights worked well and gave us easy centering on target. The trigger pulls varied somewhat, but all four rifles had essentially the same feel, weight, and dimensions. In our data, we gave the dimensions for one rifle instead of repeating ourselves. Were these all good rifles? Here are our findings.

Springfield Armory, $1,061

The street price on this gun is around $950, substantially more than any other gun in the test. Cosmetically, however, the Springfield Armory Garand had the best-looking stock of the four rifles. It was brand-new, all-walnut, and flawless, though in need of some diligently applied linseed oil to bring out its tiger-striped grain and to help preserve the stock. Within the box were an original Mil-Spec operations manual for the Garand and an excellent instruction manual by Springfield Armory, (800) 680-6866.

All the metal work was finished in gray Parkerizing. To our eyes, it seemed some of the parts were obviously redone mil-spec. Others appeared to be of new manufacture, including the Geneseo-stamped barrel. This rifle was tight throughout, including the fit of the foremost part of the wood (front handguard) to the rifle. The only other rifle which had the front wood as tight was the Lithgow, and these two turned out to be the best shooters. Was there a lesson there? We don’t know, but a National Match Garand owned by one of our test shooters also had very tight front wood. An experienced shooter told us that the best-shooting Garands he knew of all passed the “slap” test: When an accurate Garand was struck firmly with the hand, nothing rattled.

The Springfield’s wood was of excellent grain with some figure, and had sharp corners and fine inletting. The bolt was crisp and clean in operation, and the entire rifle was very well turned out. The Springfield looked almost too good. It didn’t look like it had seen any service at all, and that detracted from its appeal for some of those who examined all four rifles. They preferred a rifle that had some obvious history.

Close inspection of the muzzle with an 8x loupe revealed the rifling looked almost new. We suspect it was, because of the previously mentioned stamp on the breech of the barrel. The same close look at the other rifles revealed varying degrees of cleaning wear, from very slight on the CMP International Harvester, to noticeable on the Lithgow, to severe on the old Springfield “gunshow special.”

The two-stage trigger pull measured just under 7 pounds, but was very creepy. (The first stage of all four rifles required about 4 pounds of pressure to move the trigger far enough to contact the sear.) We tested the four rifles with Winchester Supreme 150-grain Power-Point Plus, Federal Classic 150-grain Hi-Shok, and U.S. 1966 Lake City M2 military surplus ball ammunition loaded with 150-grain bullet and 48 grains of a tubular powder, with crimped-in and sealed primers, sealed bullets and annealed cases. (The CMP surplus ammo is $88 for 400 rounds plus $17 shipping and handling. For more information, check www.odcmp.com/Services/Rifles/ammo.htm.)

On the range, the Springfield easily shot into 1.5-inch groups with the Winchester and Federal ammo. With the surplus ammunition we got a nasty surprise. This Garand wouldn’t feed mil-spec ammo reliably into the chamber. Several rounds stuck, and it required much force to get them out of the chamber. We carefully checked for an obstruction within the chamber, but it was clean. Several rounds went far enough into the chamber to permit the hammer to fall without firing the round, leaving only a slight mark on the primer and the bolt jammed in place. Could this rifle have a “match” chamber that prevented normal ammunition from entering? Checking the literature packed with the rifle revealed no such limitation.

[PDFCAP(2)]By single-loading, we were able to get one decent group on the paper with the mil-spec ammo. It measured 1.4 inches. This rifle sure didn’t hurt for accuracy.

We looked into the problem. With the bolt held open, we placed numerous mil-spec rounds by hand into the chamber, pressed them forward, and then tried to remove them. Some of them had to be pried loose with a knife blade. Others fell out. We measured several of the sticky rounds against the ones that came out easily, and the sticky ones had longer cases, measured from the base to the neck. All were well under the maximum permissible length for the cartridge. We then pulled the bullet from one of the sticky rounds, dumped the powder, and marked the case as a dummy. We then trimmed the case neck about ten thousandths, reloaded the bullet, and tried it in the chamber again. Presto, the cartridge no longer stuck. We concluded the chamber had insufficient neck-length clearance for SAAMI-spec cartridges.

The Winchester and Federal ammunition had severely crimped case necks, so there was no initial interference in the Springfield’s chamber. All the modern commercial ammunition had fed and fired. Poking through the fired cases, we found several that had primers showing signs of excess pressure (flattening, extrusion into the firing pin hole). Several of those fired cases would not accept the entrance of a .30-caliber bullet. Yet the fired cases were all within maximum-length specifications for the .30-’06 cartridge. The only way for once-fired brass from commercially loaded (SAAMI-spec) ammunition to fail to accept a bullet is for the neck dimension of the chamber, in the rifle in which the cases were fired, to be too short.

Springfield’s customer service department told us that if any part of the gun wasn’t functional, warranty work would cover the repair.

Lithgow M-1, $750

What at first glance appeared to be even better wood than that on the Springfield Armory rifle turned out to contain a bit of lighter-colored wood (not quite sapwood) on the top of the butt stock. The wood was new, with no dings or scratches. The top of the forend was birch, the rest being walnut. The wood on the Springfield had been all walnut, which gave it a slight appearance edge. A bit of linseed oil brought out the grain to good advantage. The metalwork was well finished except for a bit of wear near the muzzle, a ring of near-white metal surrounding the wood just back of the muzzle, and whiteness on the second ring around the forend. The Parkerizing was not all of the same color, as it had been on the Springfield.

The rifling at the muzzle was noticeably worn, down into the barrel. Most shooters clean Garands from the muzzle, and if a protector is not used, the muzzle will show wear. This area ought to be inspected carefully before you buy any Garand. However, the wear on the Lithgow didn’t appear to affect accuracy much. (Another cleaning option is to use a pull-through product, such as those offered by Otis, www.otisgun.com.)

The rifle (which came from Interstate Arms, [800] 243-3006, www.interstatearms.com) was fairly accurate with two of the three types of ammunition tested, and not bad with the third. Apparently the rifling was worn evenly into the muzzle, and acted like a deep crown. A counterbored crown would cure most of this, if the shooter desired. However, recrowning would probably be more trouble than it was worth, unless the job could be done without removing the barrel.

The Lithgow had a milled trigger guard, unique among the quartet, the remainder of which had stamped guards. Other than that, we could not find much different about this Aussie-made Garand.

On the range we found the windage knob didn’t grab its serrations firmly enough to hold the adjustment. This was quickly cured by tightening the opposing lock screws, one at each end of the adjustment rod. The trigger of the Lithgow was the second-best of the four rifles, breaking cleanly at 6.5 pounds. We found it was easy to get groups smaller than 2 inches at 100 yards with two of the types of ammunition tried. With Winchester and Federal ammo, most groups were around 1.5 inches, more than good enough for a randomly selected rifle of this type. With the surplus ammunition the rifle averaged 3 inches. There is, of course, no guarantee the next rifle will shoot as well, and that’s something the individual buyer will have to assess for himself.

CMP Service Grade M-1 Garand, $550

The Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP) is alive and well. If you are an active, serious, competition shooter you will be able to buy one of these arsenal-reassembled rifles for yourself. Rather than take up space here with a lengthy list of qualifications, we recommend you visit the CMP website at www.odcmp.com, or call them toll-free at (888) 267-0796 and request a product catalog. In a nutshell, to qualify to buy a rifle from the CMP you have to be 18 or over, a U.S. citizen, a member of a CMP-affiliated club and have been active within the past five years in rifle competition. The available rifles currently include M1 Garands, 1903 Springfields, and Kimber .22 LR target rifles. The catalog also lists accessories, spare parts, tools, and both surplus and commercial ammunition.

The Garands are offered in two grades, Service and Rack ($400). Service grade is slightly better, and that’s what ours was. As the CMP catalog puts it, the rifles are authentic if not pretty. This one had a distinct aura about it.

The all-walnut stock showed some nicks and dings, but was pretty good-looking, overall. The wood finish was varying degrees of old linseed oil, powder residue, and dirt. That foremost piece of wood at the front of the stock, the front handguard, was very loose. A bit of loving refinish work would have done wonders for the stock, but there were a couple of severe gouges that would require filling or inletted bits of wood to make them go away. Replacement stocks, we’re told, are available for as little as $60. This stock would be worth refinishing, and it would be an easy job. There was no pressing need to do so, and of course you’d lose part of its sense of history with the refinish. The stock on the fourth rifle, tested below, would be better off being replaced rather than refinished.

The metalwork was uniformly finished, though the butt-plate finish was a bit thinner than the remainder. The rifling was very good right up to the muzzle. We thought this rifle would benefit from glass bedding by a qualified gunsmith like Clint McKee at Fulton Armory. There was no reason for this rifle to exhibit the mediocre accuracy it did.

The trigger pull was just under 7 pounds, and fairly clean. Yet in spite of its good-looking barrel and fine trigger pull, the I.H. just didn’t want to shoot all that well. Our best three-shot group (2 inches) was with Winchester ammo. Worst was 4 inches with the same ammo. Surplus fodder gave us groups around 2.5 inches. The gas tube was slightly loose beneath the barrel, and that might have been another inaccuracy culprit. We don’t pretend to know what makes a Garand shoot. A brief search of the Internet told us there’s a lot of art to that job, and not everyone knows how.

Surplus M-1 Garand, $450

This one, a Springfield dating from the Korean-War era, looked like a dog. The stock was distressed from stem to stern. Both sides of the butt stock had been rubbed with extremely coarse-grained sandpaper right down to bare wood, but the sanding was done across the grain, leaving deep scratches that would be very hard to remove. Not a single square inch of the stock was without distress marks, dings, scratches and the like. It was as though the rifle had been tumbled with many others in a huge bin.

The metal had no finish in some areas, pitting in others, and there was no uniformity whatsoever to the metal finish or color. There was visible roughness within the barrel, and the rifling was gone for the first eighth-inch or more into the muzzle. At first glance, there were no saving graces to this rifle. Yet it fired reliably, and actually was not bad for accuracy with the Federal ammunition. In short, as bad as it looked, it would do to fight a war.

Question is, was the rifle worth its cost? The trigger broke at 6 pounds extremely cleanly, and was actually the best of the four rifles. As with the I.H. rifle from the CMP, there was a bit of looseness to the gas tube, and the forend wood was loose. If we owned this one we’d tighten those two items and see if the rifle would shoot better, but we strongly suspect this one’s barrel is beyond saving.

Our best three-shot group at 100 yards was 1.5 inches with Federal ammo, and the worst was nearly 5 inches with Winchester. The old dog shot the surplus ammo into groups of about 2.5 inches, but with the surplus ammo there was one failure to feed that we could not explain. The rifle fired, but the bolt didn’t come back far enough to pick up the next round, which left the chamber empty. We could not get the rifle to repeat that problem, so it may have been operator error in loading the clip, or its placement within the rifle. We called this one a 3-inch rifle, which wasn’t all bad.

What this rifle probably needs is a new stock and barrel, plus refinishing of the metal while you’re at it. Unfortunately this work would take the rifle’s overall cost well beyond that of the CMP rifle and probably beyond that of the Lithgow, and is therefore probably not worth doing.

Gun Tests Recommends

Surplus M-1 Garand, $450. Don’t Buy. For roughly $100 more, you can get a very good rifle from the CMP. We see no reason, other than availability of the CMP gun, to go into the surplus market and buy what was in our test the worst-looking Garand around.

Springfield Armory Garand, $1,061. Don’t Buy. Our test sample failed SAAMI specs, and should never have left the factory. The too-short neck dimension resulted in excess pressure. In our opinion, Springfield will have to make this dangerous chamber right before the rifle is fired again.

Lithgow (Australian) new M-1, $750. Buy It. There were no surprises here. The rifle performed reliably, and with enough accuracy. If we owned it, we’d tighten the front handguard and try it again for accuracy. In spite of its new stock, the rifle had its share of charm, not the least of which was its Aussie origins. We liked the looks and performance of the Lithgow, thought it represented good value for the money, and would Buy It.

CMP Service Grade M-1 Garand (International Harvester), $550. Best Buy. This CMP rifle was our first choice of the quartet. It looked authentic, with just enough wear to speak volumes of an active but not destructive service life, and its cost was half that of the (rejected) new-looking Springfield. Also, you’d save about $150 over the cost of the Lithgow. We feel that pursuing the CMP program offers one of the best ways of acquiring a Garand. You’ll know the rifle is safe and sound, and you’ll have your choice of maker, but of course you won’t know the ultimate worth of the rifle as a shooter until you shoot it. All CMP rifles are inspected for headspace and degree of wear, etc. The rifle we tested had not only an aura of authenticity, but an excellent-looking barrel and acceptable wood.

Also With This Article

[PDFCAP(3)]