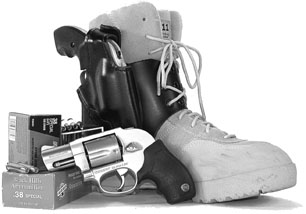

It isn’t always possible to find two or more guns that match up perfectly, but in this comparison of snub-nose revolvers, each product is comparable nearly point for point. Both the Taurus 851 SSUL (stainless steel Ultra Lite Protector) and the Smith & Wesson 638-3 revolvers carried five-shot cylinders chambered for .38 Special in the smallest frames available from their respective manufacturers. These frames were constructed with aluminum alloy, and each was given a finish to resemble stainless steel. In terms of weight, both models were slightly heavier (but less expensive) than the titanium and scandium models that are also available from Smith & Wesson of Springfield, Massachusetts, and Taurus International, which is based in Miami.

Also, each gun relied upon a coil mainspring. Revolvers in the Smith & Wesson lineup with frames larger than the 638-3’s J-frame utilize a single leaf spring to power the hammer drop. But all the Taurus revolvers regardless of size feature a coil spring, and this has a lot to do with trigger feel. Coil mainsprings tend to introduce an increase of pressure to the trigger before letting off. This is referred to as stacking. Stacking can be a negative trait, or it can actually speed up your shots, depending on workmanship or how the design is executed. In this case neither gun had an advantage.

The distinguishing characteristic in this test turned out to be the shrouded hammer design. Shrouding, or extending the frame to cover all but the tip of the hammer, was one of the earliest innovations for concealed carry. Enclosing or shrouding the hammer was one way to keep the hammer tang from snagging on the lining of the concealing garment. In fact, Smith & Wesson refers to its shrouded-hammer J-frames revolvers as Bodyguard Style and has registered that name.

With the purpose of self-defense in mind, each gun was rated for use with higher-pressure ammunition, referred to in this case as .38 Special +P. Accordingly, we tested exclusively with hollow-point ammunition. We chose 110-grain Federal Hydra-Shok, 129-grain Federal Hydra-Shok, and 125-grain new manufacture rounds from Black Hills ammunition. All but the 110-grain rounds were labeled +P.

Unlike “hammerless” models, such as the Smith & Wesson Centennial and the Taurus CIA small-framed revolvers, we were able to thumb back the hammer for single-action only fire. We took advantage of this option and sought to push the limits of their 3.4-inch (average) sight radius by shooting five-shot groups from a sandbag rest at 15 yards. But we followed up with a rapid-fire test of “two to the body and one to the head” at 7 yards to get a feel for the guns’ close-quarters capabilities. Here is what we found.

[PDFCAP(1)]

Taurus International sells so many different revolvers, it sometimes gets confusing. On the Taurus website page listing small-framed revolvers, the 851 SSUL is described as stainless steel. But clicking on the statistics page we found that this refers to the finish rather than actual frame construction. The statistics page is also where we found out its given name of the Ultra Lite Protector. We measured the barrel length as being 2.1 inches long, rather than the listed 2.0 inches, likely because we simply measure from forcing cone to the end of the muzzle with a dial caliper. Our concern was not so much length of rifled surface as it was the amount of space it took up in the holster.

The rubber grip completely covered both the front and rear strap and cushioned the space to the rear of the trigger guard. The bottom of the grip was cut short even with the frame to aid concealment. The checkered cylinder latch was contoured to assist loading and removal of spent cartridges.

Of note was the addition of a spring loaded detent in the crane and the subtraction of the ejector rod from the function of cylinder lockup. This added strength to the lockup and removed stress and friction that adds to trigger pull weight via contact with the tip of the ejector rod. Also, should the ejector rod become bent, there was less likelihood that it would interfere with cylinder rotation. This could be significant because the ejector rod of the Taurus 851SSUL was enclosed on three sides beneath the barrel.

The front sight was the typical ramp design machined as part of the barrel shroud and lined to prevent glare. But if the shrouded-hammer snubbie is an old invention, then the adjustable rear sight on the Ultra Lite Protector is the latest innovation. Adjustment is by a small screw on the right side of the frame. We turned it clockwise to move the sight blade left and counterclockwise for shifting it to the right. At the range we found that point of impact could be moved more than 2 inches left or right at a distance of 15 yards. The adjustment relied upon friction to stay in place without clicks. Aside from the value of windage adjustment, we found that the rear blade, which was blued in contrast with the frame, afforded a much better sight picture than a simple notch in the top strap. In fact, we found the sight picture to be so superior, we would have been satisfied had it been merely a static insert.

At [PDFCAP(2)] our first recorded data came from single-action only shots from a sandbag rest at 15 yards. The lined hammer tang, which due to the shroud appeared to be more of a sliding button, also contained the key-operated hammer lock. But the lock was unobtrusive and did not interfere with pulling back the hammer.

We found that consistent hits upon the target were a direct result of controlling recoil. Nothing new here, but some guns help you more than others. Smaller-framed guns with limited grip surface demand closer attention to follow through.

We scored five-shot groups that measured an average size of 2.8 inches with both the Black Hills 125-grain JHP +P ammunition and the 110-grain JHP Federal Hydra-Shok rounds. For some reason we managed only one sub-3-inch group with the 129-grain JHP +P Federal Hydra-Shok ammunition.

Our rapid-fire test started from low ready, then we simply engaged a Hoffners ABC16 training target (hoffners.com) with two shots to the chest, or A zone, and one to the head, or B zone, in rapid succession. Ten separate strings for a total of 30 shots were fired. For this test we used the Black Hills 125-grain JHP+P rounds exclusively. After ten strings of aggressive shooting, we found only two shots printed outside of the 7.8- by 5.5-inch A zone. Twelve of the A-zone shots formed a 5-inch group nearly dead center. In the B zone, all the shots were in line straight up or down, but one shot was missing completely. Only four of the shots were in the actual B zone, which formed the head of the humanoid silhouette, but the remaining hits would have registered a deadly score.

[PDFCAP(3)]

The 638-series J-frame revolver is smaller than the Taurus 851 SSUL by approximately 0.30 inch in length. Some of the difference can be attributed to the barrel, which measured just less than 1.9 inches long. Overall height was also about 0.2 inch less. The rubber grip leaves the back strap bare and ends even with the bottom of the grip frame or butt. This is the kind of compact profile that lends itself to all manner of concealment, even ankle holsters. Smith & Wesson calls the finish on this gun “bead blast,” but to our eyes it made the aluminum gun look like stainless steel.

The Smith & Wesson revolver weighed in at 15 ounces, 2 ounces less than the Taurus — a difference that might be traced to design differences. Most obvious was the lack of shroud underneath the barrel, leaving the ejector rod unprotected. This model did not include a crane detent and used the ejector rod for additional lockup. The ejector rod itself was noticeably shorter as well.

The Smith & Wesson 638’s rear sight consisted of a simple top strap notch without an adjustable blade. Its front sight was a lined ramp integral with the barrel shroud. This model also included a hammer lock, which was key-operated from the left side just above the contoured and checkered cylinder release. With the cylinder and crane opened, we saw the numbers 638-3 imprinted on the frame. According to Smith, the dash-3 suffix referred to the milling lug used to form the frame.

At the range we discovered that there were two ways to approach the long double-action trigger press on each of these guns. We could pull straight through, with the last bit of travel giving us the sensation of speeding up, or we could stage the trigger. Staging refers to pausing during the double action press just before let-off, almost as if we were presetting the hammer into single action but without touching the hammer. The Taurus revolver was more difficult to stage and preferred to be shot quickly in double-action mode. The Smith & Wesson was happy to oblige with either technique.

But no matter how we shot the 638-3, we found that the key to controlling the elevation of our hits was mastering the grip. The side panels are rounded to fill the palm, and we felt this encouraged the gun to rotate upward in the hand. This served to take up some of the recoil, but a firm grip and a locked wrist were more effective.

At the 15-yard bench, we found the Smith & Wesson to be slightly more accurate than the Taurus 851SSUL. Firing the 125-grain Black Hills and the 110-grain Federal ammunition produced a dead heat in the size of our five-shot groups. But the 129-grain Federal Hydra-Shok ammunition was the tie breaker, with the best performance overall. Strangely, our Oehler chronograph told us that average velocity from this ammunition was the same in both guns, but the accuracy of the Smith & Wesson was much better, about 2.4 inches on average.

However, we couldn’t help but notice that debris was being spit from the break between the cylinder and the forcing cone. A check of barrel and cylinder alignment with a match quality range rod told us that the timing on each revolver was sound. But we also noticed that the inner diameter of the barrel on the Smith & Wesson was much tighter than the one found on the Taurus. Perhaps this was causing unburned powder or particles of the bullet to be blown aside rather than entering the forcing cone.

In our 7-yard rapid-fire test, the smooth trigger action helped us keep the shots in line vertically. But our three misses to the center-mass A zone all printed high. In the head area, or B zone, we were either low or high 80 percent of the time, as we seemed to either bear down too much on our grip or relax and let the muzzle travel upward on recoil. After shooting so well from the bench, we expected better, and this may have been our downfall. Perhaps the Smith & Wesson had given us too much confidence, and we simply needed to slow down.

Gun Tests Recommends

• Taurus 851 SSUL Ultra Lite Protector .38 Special, $461. Our Pick. A new snagproof rear sight that provides windage adjustment and a superior sight picture enhances this gun’s versatility. We think more revolvers should offer this design.

• Smith & Wesson 638-3 .38 Special, $620. Buy It. This revolver is a classic. Its double-action trigger is smooth and predictable to the point of offering fast action or a careful press. Lighter and smaller in length and height than its competitors, this gun deserves serious consideration.