The 38 snubnose revolver is a staple of murder mysteries, cop TV shows for many decades, and of real-life cops who need a good, light backup. Everyone over the age of, say, 40 has seen a snubby at one time or another. Todays TV cops favor all manner of automatic pistols, so the snub 38 is not often seen. But that doesnt mean its no good. The bottom line is, if all you have is a 38 Special snubnose with only five shots, you are a very long way from being unarmed. If you carry five more in a speed loader, well, what more could you want?

Its clear that Smith & Wesson figures theres still a viable market for the snubnose 38, because it has come out with a new revolver called the Bodyguard 38, usurping the name of the previous Bodyguard with shrouded hammer. The new Bodyguard 38 comes with an “integral” laser sight, and the gun vies with the Centennial Airweight for looks, charm, effectiveness, concealability, and price. We acquired a new Bodyguard 38 No. 103038, $625, with an eye toward pitting it against two good wheelguns already in the S&W arsenal, a used, older Centennial Airweight (street price around $400) and a Chiefs Special Model 36 with square butt (street price about $300) that had its hammer bobbed, so it was essentially a double-action-only gun like the other two, though it was still possible to cock the hammer. All the guns were S&W five-shot 38 Specials, and all had 1.9-inch barrels. Our prime interest was to see if the newer, more expensive Bodyguard was worth the money when proven, perfectly servicable older guns are readily available at gun stores, pawn shops, and gun shows.

The snubby has a lot of advantages and not many disadvantages. The snub 38 is not a target revolver, so dont expect it to make small groups for you, despite the fact that some have been fitted with adjustable sights. In this test, we looked at these guns as self-defense choices, and nothing else. We noted its not particularly easy to conceal a snub 38. In fact, many 45 autos are slimmer, thus more easily hidden. But you can simply put the 38 revolver into your pocket, no holster, and no one will know what that odd bulge really is. The absence of a hammer on this trio of test guns makes them easy to get out of the pocket, too.

We tested the trio with four types of ammunition, and tried several more types of loads, which are unreported. Our official test loads were Winchester 130-grain flat-nose FMJ, PMCs 132-grain round-nose FMJ, and Blazer 125-grain +P JHP. We were unable to obtain any heavy-bullet factory loads, so we used a handload featuring a 158-grain cast SWC. Heres what we found.

S&W Model 442 Centennial Airweight

38 Special, $400 (used); $616 (new, No. 162810)

S&W offers a machine-engraved version of the 442 for just over $900 MSRP, but it lacks the barrel rib of our test gun. Also, SKU #178041 is the newly made Centennial Airweight, unadorned and matte black with stainless cylinder, which lists for $640. Or you can buy our matte-black test gun-No. 162810 with a carbon-steel cylinder-for $616 new.

This mostly matte-black revolver had hard-rubber grips with a finger groove that most of us liked. The grip was comfortable in the hand, and although we could get only two fingers onto it securely, we had no trouble controlling the gun. The DA trigger was case colored, and had no serrations so the trigger finger could slide sideways during shooting, though we did not find that necessary nor desirable. Although the frame was aluminum and the cylinder and barrel were steel, the finish was extremely uniform all over. The right side of the frame had the Airweight name laser-etched into it along with the S&W logo, and all filled with white paint.

The gun opened by the usual S&W latch, which we found did not cut our fingers nor get in the way to any extent during our shooting tests. As with all older S&W snubbies, the empties were lifted only 0.625 inch out of the chambers, but if you had a clean chamber, the empties could generally be thrown out of the gun by working the ejector briskly. The ejector rod was steel, and formed the forward latch for the cylinder. The rear of the cylinder had the usual spring-loaded pin fitting into a hole in the rear of the frame for the latch.

The fronts of the cylinder were relatively sharp, though they could have been rounded to avoid cutting fabric or holster. The sights were bold and wide, but there was not enough room on the sides of the front sight blade, and it got lost easily during our fast shooting sessions.

On the range we found the Centennial shot close to its sights for elevation with all the test loads, and grouped about 2 inches to the left at 15 yards. With a few trial FBI loads from Buffalo Bore, the shots struck somewhat higher, but still on the paper. The Centennial Airweight did best with our handload, giving round groups that averaged 2.4 inches. The trigger of this gun was the best of the trio for deliberate slow fire. The trigger stacked to the letoff point, and we could then fine-tune our sight picture and finish the press. Still, our groups averaged around 4 inches at 15 yards.

Our Team Said: Overall, this revolver felt the best to our group, in part because it had the best DA trigger for precision slow shooting. The gun performed better in slow DA shooting than the custom M36, even when the latter was fired single action. All rounds struck slightly left of center, but the Centennial was well regulated for elevation with everything but a few FBI loads, which struck high. All loads struck about 2 inches left of center, which we considered acceptable for this type gun.

S&W Model 36-1 Chiefs Special Custom

38 Special, about $300

Original production of the Model 36 or Chiefs Special began in 1950 and ceased in the early 1990s. The square-butt version came along in 1952 in an effort to give better control. The Model 36 was offered recently as a remade Classic from S&W, for $822 MSRP, and there are still plenty of good used ones around. We have seen a few original Model 36 revolvers in near-perfect shape go for about $500, and one in decent shape for $400, so our best guess for this altered but not reblued gun is in the $300 range. Condition determines all. If you find a used one, check for tightness and also look for gas cutting on the top strap right behind the forcing cone. That tells you how much its been shot.

Ours had been altered, carried, but not shot much nor had it been reblued. It was possible to cock it by pressing the trigger carefully and catching the hammer with the thumb. Then the gun gave a 2.7-pound trigger pull. To lower the cocked hammer, grasp it firmly with thumb and finger on its sides, press the trigger, and gently lower the hammer. We do not recommend using a gun altered in this manner in any way but double-action only. In fact we found no significant difference in our groups, to our surprise, between single- and double-action shooting.

This all-steel gun had a high-polished blued finish, case-hardened hammer and narrow trigger, and checkered walnut grips. There was room for all our fingers on the squared grip, and that was a great help to fast shooting. The slightly extra weight of the all-steel structure helped there too, but in all our shooting we could not detect any significant difference in felt recoil between any of the three test guns. Thats maybe a testament to the success of their grip shapes and grip materials.

The front sight was serrated and rather narrow, with a corresponding narrow notch cut in the top of the frame for the rear sight. All three guns didnt have enough room on the side of the front blade, in our opinion, but this one at least had had red paint applied to the front blade, which greatly helped us see it during fast shooting. This Chiefs Special was old enough to have a pinned-in barrel, and the fit and finish were excellent everywhere. The crane had the least gape of the three guns when the cylinder was pressed sideways.

The lockup in the firing position was not quite as good as that of the Centennial, and both were much tighter than the brand-new Bodyguard. The DA trigger pull was relatively smooth, but not as predictable as that of the Centennial. We didnt expect tight groups and were not disappointed.

At the range we came to like the bigger grip, though it didnt help us shoot slowfire at all. Some groups with Blazer and PMC were about six inches at 15 yards. This revolver was the best for fast shooting, thanks to two advantages. One was the red-painted front sight, which was by far the fastest to pick up. Two was that it had a grip that we could grab with all our fingers, and that paid off very well during extremely rapid DA shooting. We could shoot this gun faster than either of the other two revolvers, at close range, with good hits.

Our Team Said: We downgraded it largely because its been altered, which we dont recommend. Also, its not easy for a non-expert to determine if a used gun is good or not, and such people probably ought not to buy used guns. Weve seen a bunch of really shot-out and loose snubbies over the years that would probably tend to shave bullets, and thats not a good thing. We dont recommend cutting the hammer for any reason. You can buy several hammerless snubbies today, so theres no reason to alter the hammer. If you find one of these with an intact hammer, we suggest you might want to carry it in a holster, not your pocket.

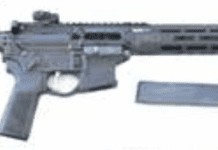

S&W Model 438 Bodyguard 38 Special, $625

Its light! Its plastic! And it shoots real bullets. Those were our first impressions of the matte-black steel-polymer Bodyguard 38, and there were plenty more.

First, how do you open it? That was new. On top of the rear of the gun is a plastic shroud that you can shove forward easily with the thumb of either hand, though its easier with the right-hand thumb. In fact, we found it difficult to get the cylinder to swing out with the gun in the left hand, compared to the right thumb and forefinger getting it open very easily.

On the right rear of the frame is the laser, which is held on by a tiny Torx-head screw. To turn it on, press down very firmly on a small button on top of the unit. One press gets a steady light, the second press gets a pulsing light, and the third push turns it off.

The upper frame was aluminum, and the lower portion was steel-reinforced polymer. The grips were one-piece hard rubber. The factory claims the cylinder and barrel are stainless steel, though we found them to be a magnetic variety of stainless. The fronts of the cylinder were beveled much like early Colt SA revolvers, which we thought was a good thing.

Another good thing was we could really get a good hold on the grip of this revolver. We believe the grip will sell a lot of these to ladies or to anyone with smaller hands. Some of us would have liked them fatter like on the Centennial, but we found they worked very well.

Opening the cylinder revealed more new stuff. The latch consists of only a single pin contained within the star on the back of the cylinder, which is caught into a hole on the recoil shield that is in the center of a mating star that actually turns the cylinder. Gone are the typical hand of every other S&W in the world before this iteration. Also gone is the lockout of the action when the cylinder is open. The action cocks and drops the hammer any time you press the trigger.

At the front of the cylinder is more news, some of it good. The ejector has much greater travel, at least a quarter inch more, so getting empties out is not the chore it sometimes was with earlier models. The slim steel ejector rod is protected by a wrap-around shield under the barrel. However, theres no lockup at the cylinder front, and the crane gapes quite a bit for a new gun. The cylinder is also not very tightly locked with the gun in the just-fired position. The chamber could move about 0.020 inch sideways, at least twice as much of the worst of the other two.

But on the range we found the looseness didnt make a whole lot of difference to the guns accuracy. All in all, it turned in some of the best results, but not by much. Our first surprise came when we dropped in two FBI loads, closed the cylinder and tried a shot. The gun didnt go off. We discovered the cylinder turns backwards from every other honest old S&W made in the last 100 years. The cylinder is rotated by a star-shaped device on the recoil shield that is spun internally as the trigger is pulled. It worked, but took some getting used to. The barrel had segmental rifling, with rounded corners. This is an excellent way to make a barrel, as Alexander Henry discovered well over a century ago.

The trigger pull was slick and smooth, but gave little clue when the gun would go off, and, surprisingly, we liked that. Shooting the gun as fast as we could, we noted it was a bit slower than the M36 because its light weight was noticeable, as the gun rose more than the heavier gun. We didnt like the iron sights any more than those on the Centennial, but then, there was the laser.

Undoubtedly the laser is a psychological advantage for the shooter, especially at night. Theres no need for night sights. Just press the dot and light up your target. We found it unnatural to trust the laser during hip shooting, but it did work and we could see its advantages. We didnt like the button that turned it on, but in fairness it was stiff enough that the laser wouldnt be accidentally turned on in your pocket, burning the battery to zero. But the laser does shut itself off automatically after five minutes. We had no use for the second, pulsing presentation of the laser. If youre shaking even slightly, its impossible to tell your laser from that of a second one, no matter that one is pulsing and one is steady. However, we guessed that if the pulsing laser were seen dancing on his chest by a felon, he might think of it as a ticking time bomb, drop his gun, and run.

Our Team Said: We liked the gun, despite construction methods and materials that are alien to lovers of classic S&Ws. For not too much money you get a light gun, easily carried, that can handle hot +P loads with ease, shoots well, and has the advantage of a laser. Earlier S&W snubbies can be fitted with Crimson Trace laser grips, but they are pretty costly. We thought this was a fine system, and the laser is of course easily adjustable to your point of impact. The iron sights here put most rounds about 8 to 9 inches high and 2 inches left, and for that we gave the minus sign on our grade. The pinned-in sight could be replaced with a higher one, but you ought not to have to do that.

0910-38-SPECIAL-ACC-CHRONO-DATA.pdf