How much do you need to spend to get into the Cowboy Action game? Sure, you can spend lots on fancy duds, and that’s a big part of that game, but the bottom line for participation is a good set of guns, not the least of which is the revolver. The most common caliber for today’s “cowboy” is still the .45 Long Colt, just as it was a century ago with the original riders of the range. Even if you don’t anticipate becoming a weekend cowboy and shooting in any of these events, a single-action .45 makes a lot of sense. They’re practical outdoor-carry guns, not entirely useless for self-defense or home protection, and they are lots of fun to shoot.

In the June 1999 issue of Gun Tests we compared a few commonly available .45 Long Colt SA handguns, and the winner was the antique-finished $518 Cimarron Model P, with 4.75-inch barrel. That gun’s finish and just-right feel were prime movers in our decision to place it above its competitors.

But there are always other guns we’re curious about, and we always want to see how our previous winners stack up against other products in the niche. Thus, we put the Cimarron up against two increasingly popular and fairly new offerings in .45 LC, the $599 Colt Cowboy and the five-shot $1,492 Freedom Arms Premier Grade Model 1997. Although the five-shot limitation of the latter makes it unsuitable for Cowboy Action events (they usually mandate one empty chamber), the Freedom is popular with those who like the cartridge and want a top-quality gun for it. Here’s what we thought of the guns.

Colt Cowboy

Our recommendation: We liked the $599 Colt Cowboy and recommend it heartily. With prices of mint 2nd Generation Colts approaching $3,000, the Cowboy offers lots of gun at an affordable price.

We’d heard that the Colt Cowboy didn’t look at all like a “real” SA Colt, so we were pleasantly surprised when we opened the box containing our gun, sent to us by Ray Meibaum, one of the premier purveyors of single-action Colts. Meibaum, who knows Colt Single Actions inside and out, agrees with us that the Cowboy looks very much like the old SA. In fact, we put it side-by-side with a mint-condition 2nd Generation SA Colt and found it hard to see any difference—until we cocked the hammers.

The new hammer has a cutout for a transfer bar between the hammer and the frame-mounted firing pin. Everything else about the Cowboy seemed to be pure SA Colt. In fact, we had both the Cowboy and the 2nd Gen. Colts on our desk, and frequently picked up one thinking it was the other, they look and feel that much alike.

The metal polish on the Cowboy was excellent. It had flat sides, sharp corners, and no rippling along the barrel. The bluing was superb. The dark case coloring, while a bit milky, was more than adequate. It should age well. The cylinder, barrel, ejector rod housing, trigger, guard and backstrap were blued. The frame was case colored. The hammer was blued, then polished white on the sides. The stocks were plastic copies of the early Colt hard rubber grips, checkered black with rampant Colt medallion at the top. They were slightly larger than the back strap, but a perfect fit elsewhere. We couldn’t fault the metal work or the overall appearance. All the fitted metal parts were well mated, with no slop or rattle.

The gun locked up tightly when cocked, and the timing was near-perfect. If you cocked it very slowly with drag on the cylinder, it was just possible to prevent the bolt from dropping into place. Though many make a big deal out of this, in practice it isn’t a problem. The mass of the loaded cylinder spins the cylinder into lock when the gun is handled normally. What is important is that the cylinder be held immobile while the hammer falls, and the Cowboy was extremely good in this respect. One odd thing we found on our sample was that every single screw on the Colt Cowboy, right out of the box, was slightly loose. The only other potential problem we could see is that with the hammer in the loading/unloading position, the trigger is held farther forward than the ordinary Colt SA trigger. If you’re in a hurry to get reloaded, or if you have thick fingers, that might slow you up a trifle. Otherwise, the checkering on the hammer made it very easy to cock.

Comparing the Cowboy’s cosmetics to a 2nd Generation Colt’s, we found a slight difference in the hammer shape, and that’s about all. As you cock the hammers, you hear a big difference. You get only three clicks as you cock the Cowboy’s hammer, but that’s because you don’t get—or need—the safety position, which is the first click of the original SA Colt. The transfer bar permits you to carry all six chambers loaded. If you drop the gun on a rock, or vice versa, the gun can’t fire. The cylinder outlets of the Colt Cowboy measured 0.458 to 0.461 inch. The Cowboy’s groove diameter measured 0.452 inch. This combination of loose cylinder outlets and tight bore made us think the gun wouldn’t shoot worth a darn. We were proved wrong, at least with two of the test loads. The Colt hated the Remington load that the other two guns thrived on, but put the Black Hills and our handload into groups than rivaled those of the super-tight, ultra-precise Freedom Arms gun.

Loading and unloading the Colt was a snap because the cylinder lined up with the loading port perfectly, when you backed the cylinder up against the hand. The drill to unload a SA handgun (except Rugers) is to index the cylinder until it clicks to the next chamber, back the cylinder up against the hand and hold it there, then hit the ejector rod. Repeat as needed. This technique gets a single-action handgun unloaded very quickly. With the muzzle elevated, empties ought to slip right out, and with the Colt Cowboy they did just that.

The trigger pull was rough and heavy. It broke at 6.0 pounds. This good-looking Colt would benefit greatly from a trigger job, in our estimation. The sight picture was much better than that of the old Colts, with a wider front blade and slightly wider rear notch. These are not target sights, but are more than adequate for the type. The Cowboy shot darned near exactly where it looked, at 15 yards range. The Cowboy Action shooter will like that, and so would Bat Masterson.

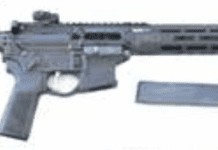

Freedom Arms Model 1997

Our recommendation: Nobody makes handguns tighter or cleaner than Freedom, and few companies make them shoot as good, much less better, for a given caliber. This doesn’t mean Freedom’s Model 1997 .45 Long Colt is perfect, and it’s not really suited to Cowboy Action competition, but it’s a doggoned good handgun.

Dark red “wine-wood” laminated grips that seem to grow out of the stainless grip. Zero slop in anything, whether or not it actually moves. No perceptible end-play in the cylinder. Exactly no motion to the cylinder when the hammer is cocked and the gun is ready to shoot. Line-bored cylinders. Perfect, glare-free yet attractive polish to the white-finished steel. Zero creep to the 3-pound trigger pull. Action sides that are hand-stoned to a perfect flat fit with the trigger guard and backstrap. Adjustable sights that index tightly from click to click and lock in place like a bank vault protecting your money. Put all this together and you know you’re handling a Freedom Arms Premier Grade revolver. That’s the performance you get for your $1,492.

Because it’s a five-shooter, the small-frame Model 1997 won’t be used by Cowboy Action shooters—unlike its greatly popular six-shot .357 Mag brother of the same frame size—because you’re usually required to leave an empty chamber under the hammer with a gun of this action design. Not many competitors would give up one round in the gun to their opponents. The Freedom has a built-in, nearly invisible, transfer bar that might permit safe carrying with all five chambers filled. However, Freedom Arms Co. recommends carrying the gun with only four rounds loaded.

This all-stainless revolver feels much lighter than either of the other two test guns. It’s actually 0.7-ounce lighter than the Colt Cowboy, and 0.3-ounce heavier than the Cimarron Model P. The absence of the steel needed for the sixth chamber helps achieve this gun’s slight muzzle-heavy steadiness on target. A handy and well-fitted SA .45 revolver with adjustable sights, as this one had, is a natural for the field. This one came with an alternate (extra cost) cylinder chambered for .45 ACP, which increases the gun’s overall utility. We didn’t try the gun seriously with the .45 ACP cylinder, but our limited testing indicated outstanding accuracy.

[PDFCAP(3)].Although the Freedom 1997 is drilled and tapped for a scope base, with the holes hidden under the rear sight, we suspect most of these guns will never have a scope mounted on them. The added weight and bulk would kill the balance and compactness of the handgun.

The grip angle is different from that of a Colt, and the gun doesn’t rise in the hand quite as much or as easily, so the Freedom gives the shooter’s hand a bit more kick than either of the other two guns in this test. In fact, with our handload, the Freedom was very unkind to several of our shooters’ hands. On the plus side, the grip shape kept the cocked hammer well away from the web of the shooter’s hand, unlike the hammers of the other two guns. Although the Freedom 1997 laid ‘em in there darned near as well as we could hold, we didn’t enjoy shooting our handload, which launched a 250-grain bullet at more than 1,000 fps. That is only beginning the hot-.45 realm, with much hotter factory .45 Long Colt loads available over the counter. We suggest that the shooter of this gun will be much happier in the long run with normal, not maximum, loads.

The trigger was wide and smooth, and the hammer was serrated, not checkered. We’d have preferred checkering, as on the easy-cocking Colt Cowboy. Sure you can hang your thumb over the top to cock it, but we’d rather not shift our grip to cock a single action, and this hammer lets our thumb slide off the side.

Another point of contention is the retention screw for the base pin. To remove the cylinder for cleaning, you need a screwdriver. That’s not too handy in the field. Although a screw is better than a spring-loaded plunger for keeping the base pin secure under heavy recoil, we’d ask that Freedom consider a push-button release for this gun. That way you won’t risk losing the screw if you have to disassemble the gun in the field.

Cimarron Model P

Our follow-up recommendation: This $518 clone of a Colt SA looks great, fits the hand like a glove, and shoots well. However, we don’t know how long it’ll last, because our test shooting made it a whole lot looser than it was when it came in the door. Still, for the price it’s hard to beat. Treat it well without lots of hot loads, and it’ll probably last long enough.

Cimarron removes the finish from its “Original” finished Model P and distresses the wood to get it to look like an old, well-used Colt. The one-piece wood grips are here-and-there dinged up to look like the marks of honest usage. They fit the supporting metal extremely well. Everyone who saw this gun remarked how “authentic” it looks, but what they’re actually saying is that it looks like an expensive old SA Colt that has seen lots of hard use over the last 100 years or so, and instead of having the multi-thousand-dollar price tag of the old Colt, the Cimarron costs only $518. Hey, I can afford it!

We can’t fault the finish of the Cimarron because there is none, except for whatever they put on the gun to prevent rust. The overall metal fit is well done. However, cowboys didn’t carry old guns by choice. Bank robbers and lawmen alike got the best and newest handguns they could find, because their lives depended on them. Their guns got old-looking with time. Still, the Cimarron does offer that aged look, with one big difference. The innards are brand-spanking new.

The gun fits the hand like it belongs there, thanks to the excellent fit of the one-piece wood grip with their smooth finish. The Cimarron resembles an original Colt so closely, and feels so similar, that further comment on pointability or handling is needless. If you’ve handled a Colt SA, you’ve handled the Cimarron. Cimarron got lots of details on their Model P amazingly close to details of original Colts made around the turn of the last century. The trigger guard, for example, is rounded on the bottom like they were on Colt SAs of that period. The pattern of the checkering on the hammer is exactly right. The rounded fronts of the chambers are also precisely correct. Yet Cimarron could do two things to make this gun an even closer ringer for the old Colt. One is to offer a replacement base pin to avoid the look of the “safe” system mandated by import laws, and two is to make the firing pin cone shaped, which they were at that time.

Our only question about this gun concerns the heat treatment of its metal, and the expected life of the parts. We shot about 100 of our handloads in the gun. That load, 10.0 grains of Hercules Unique behind a flat-nose cast 250-grain lead bullet, CCI 300 primer, puts the bullet out about 1,000 fps. Typical Cowboy Action loads, like Black Hills’ ammunition, get about 750 fps with the same bullet. After our testing, the Cimarron’s cylinder exhibited significant rotational play, indicating that the top of the hand, or the star, or both, were getting battered from the more intense load. This handload is not all that hot, compared with some factory loads now available. Many of them are much hotter. The Cimarron was still very much more than serviceable at the end of our test, but we can’t recommend a steady diet of powerful loads for the Cimarron.

Gun Tests Recommends

Colt Cowboy, $599. This gun is not an exact copy of the old Colts, but it sure looked good in the holster and performed well in the hand. Remember, cowboys of 100 years ago didn’t pack guns that looked a hundred years old. They bought the best they could find, and the Colt Cowboy is, today, one of those. Buy it.

Freedom Arms Model 1997, $1,492. Freedom sets the standard for handgun manufacturing precision today, and the Freedom Model 1997 .45 Long Colt is no exception. However, we can only issue a conditional buy for the gun because of its price and somewhat limited use. If you want the best product of its type made, then the gun’s price is well within reason. Still, the slightly less costly Field version would be a more affordable choice. Either way, the Field or the Premier Grade would make an excellent all-purpose outdoorsman’s handgun—what the original cowboys wanted. But for current Cowboy Action events, not having access to a fifth shot is a significant downside, in our view.

Cimarron Model P, $518. As we stated in a previous issue, if you’re into the look of the old cowboy guns and don’t want to pay megabucks for an original Colt, go for the Cimarron. It looks, shoots, and feels right. Additional testing has confirmed our original recommendation, and we’d still buy it. But we would not shoot hot loads in it, and would keep an eagle eye on the wear of internal parts.